- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Read online

NAGUIB MAHFOUZ

The Day the Leader Was Killed

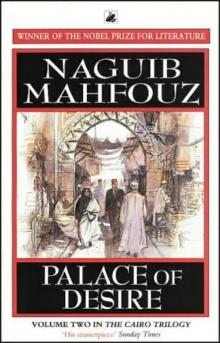

Naguib Mahfouz was born in Cairo in 1911 and began writing when he was seventeen. A student of philosophy and an avid reader, his works range from reimaginings of ancient myths to subtle commentaries on contemporary Egyptian politics and culture. Over a career that lasted more than five decades, he wrote 33 novels, 13 short story anthologies, numerous plays, and 30 screenplays. Of his many works, most famous is The Cairo Trilogy, consisting of Palace Walk (1956), Palace of Desire (1957), and Sugar Street (1957), which focuses on a Cairo family through three generations, from 1917 until 1952. In 1988, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first writer in Arabic to do so. He died in August 2006.

THE FOLLOWING TITLES BY NAGUIB MAHFOUZ ARE ALSO PUBLISHED BY ANCHOR BOOKS:

The Thief and the Dogs

The Beginning and the End

Wedding Song

The Beggar

Respected Sir

Autumn Quail

The Time and the Place and other stories

The Search

Midaq Alley

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

Miramar

Adrift on the Nile

The Harafish

Arabian Nights and Days

Children of the Alley

Echoes of an Autobiography

The Cairo Trilogy:

Palace Walk

Palace of Desire

Sugar Street

AN ANCHOR ORIGINAL, JUNE 2000

English translation copyright © 1997 by The American University in Cairo Press

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in Arabic as Yawm qutila al-za-‘im. Copyright © 1985 by Naguib Mahfouz. This translation first published in paperback by The American University in Cairo Press, Egypt, in 1997.

Anchor Books and the Anchor colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mahfuz, Najib, 1911–

[Yawma qutila al-za‘im. English]

The day the leader was killed / Naguib Mahfouz; translated by Malak Hashem.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-48361-4

I. Hashem, Malak. II. Title

PJ7846.A46 Y3813 2000

892.7’36—dc21 00-024572

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

Contents

Cover

About The Author

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Muhtashimi Zayed

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

Randa Sulayman Mubarak

Muhtashimi Zayed

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

Randa Sulayman Mubarak

Muhtashimi Zayed

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

Randa Sulayman Mubarak

Muhtashimi Zayed

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

Randa Sulayman Mubarak

Muhtashimi Zayed

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

Randa Sulayman Mubarak

Muhtashimi Zayed

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

Randa Sulayman Mubarak

Muhtashimi Zayed

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

Randa Sulayman Mubarak

Muhtashimi Zayed

Muhtashimi Zayed

Little sleep. Then a moment of expectation full of warmth beneath the heavy cover. The window lets in a faint streak of light which powerfully penetrates the forbidding darkness of the room. O Lord, I sleep at Thy command and awaken at Thy command! Thou art Lord of things. There goes the call to the dawn prayer marking the birth of a new day for me. There it is calling Thy name from the depth of silence. O Lord, help me tear myself away from my warm bed and face the bitter cold of this long winter! My dear one is bundled up deep in sleep in the other bed. Let me grope my way in the dark so as not to wake him up. How cold the ablution water is! But I derive warmth from Thy mercy. Prayer is communion and annihilation. God loves those who love to commune with Him. Blessed not is the day in which I draw not closer to the Lord.

At long last, I tear myself away from my reveries to awaken those asleep. I am the alarm clock of this exhausted household. It is good to be of some use at this advanced age of mine. Old, indeed, but healthy, praised be the Lord! Now it is all right to switch on the light and knock on the door, calling, “Fawwaz,” till I am able to hear his voice crying out, “Good morning, Father.”

I then return to my room and switch on the light there too. Here lies my grandson, fast asleep, nothing showing except the center of his face, tucked in between bedcover and bonnet. Nothing doing. I must drag him out of the realm of peace and into hell.

My heart goes out to him and his generation as I whisper, “Elwan, wake up.” He opens his light brown eyes and yawns as he mutters with a smile, “Good morning, Grandpa.”

This is followed by a rush of feet and a loosening of tongues as life begins to throb between the bathroom and the dining room. I sit and listen to the morning recitation of the Quran on the radio until Hanaa, my daughter-in-law, cries out, “Uncle, breakfast is ready!” Food is the single most important thing that remains for me out of the pleasures of life. Manifold indeed are God’s blessings in this life of ours. O Lord, protect me from sickness and disability. No one any longer to take care of anyone anymore. And no money left over in case of sickness. Woe unto him who falls! Now it is beans or falafel for breakfast. Both of these are more important than the Suez Canal. Gone are the days of eggs, cheese, pastrami, and jam. Those were the days of the ancien régime or B.I.—that is, Before Infitah, Sadat’s open-door economic policy. Prices have long since rocketed; everything has gone berserk. On a diet rich in bread, Fawwaz continues to gain weight. Hanaa too, but she is also aging prematurely. At fifty, today, one appears to be sixty.

“On certain days now, we’ll have to be working mornings and evenings at the Ministry, so I’ll have to give up my job at the firm,” said Fawwaz in his loud voice.

I grew perturbed. Both he and his wife work in a private-sector firm. Their income, my pension, and Elwan’s salary combined are hardly sufficient to meet the bare necessities of life, so how would it be if he were to leave the firm?

“It may be for just a short while,” I said in a hopeful tone.

“I’ll do some of your work for you and bring the rest home. And I’ll explain your circumstances to the Chief of Division,” said Hanaa.

“That means I’d have to work from crack of dawn to midnight,” Fawwaz retorted angrily.

I have always been hoping that we could try not to discuss our problems at mealtimes. But how?

“The father of my professor, Alyaa Samih, drives a cab in his spare time and, of course, earns much more this way,” said Elwan.

“Does he own the cab?” his father asked him.

“I think so.”

“And how would I buy one? Is your professor’s father rich or does he take bribes?”

“All I know is that he’s a respectable man.”

“When all’s said and done, he has chosen a respectable path,” I said.

“Maybe one day I’ll choose a similar path,” Elwan said, laughing.

“What would you do?” asked Hanaa in all earnestness.

“I’d round up a gang to rob banks!”

“Best thing you can do,” snapped back Fawwaz.

I wiped the dishes properly and Hanaa took them back to the kitchen. The moment they had s

aid good-bye and left, I found myself, as usual, all alone in the small flat. O Lord, provide for them and protect them from the vicissitudes of time! O Lord, grant me the grace of Thy protection! Were I to leave this house as it is, it would remain a total mess until the evening. I do what I can with my bedroom and the living room, where I while away my solitude listening to the Quran, to songs, and to the news on the radio and television. Had there been a fourth room, Elwan could have settled down in it. Praised be the Lord, I do not question His authority.

One day, Abu al-Abbas al-Mursi, the pious sage, came across a group of people crowding around a bakery in Cairo in a year when prices had risen tremendously. His heart went out to them. It occurred to him that if he had had some small change, he could have helped these people, whereupon he felt some weight in his pocket. When he put his hand in it, he found a few coins, which he promptly gave to the baker in exchange for some bread, which he went on to dole out to the people. After he had left, the baker discovered that the coins were false. So he cried out for help until he caught the man, who then realized that the feelings of pity he had felt for the people had been a sort of objection on his part to God’s ways to men. Repentant, he begged the Lord’s forgiveness and, no sooner had he done that, than the baker realized that the coins had in fact been genuine! That is indeed a perfectly holy man. Holiness is bestowed only upon those who shun the world. I am close to eighty but am unable to shun the world. It is God’s world and His short-lasting gift to us, so how am I to shun it? I love it, but with the love of one who is a free, devout worshiper. Why, then, doest Thou begrudge me holiness?

I am interested in the Quran and the Hadith, just as I am interested in the Infitah and in my beans mixed with oil, cumin, and lemon. When will I be graced with God’s boundless mercy so that I may one day be able to point to the light from afar and it would just be switched on without my ever having to touch the light switch? I have only one good friend left and, even then, old age has come between us. Solitude of the soul, of place, and of time. It is a year now since I was last able to read. I get very little sleep, but I am not afraid of death. I shall welcome it when it comes, but not before it is due.

When King Fuad inaugurated our school, I was called upon to give a speech on behalf of the teachers. A day of glory. My heart warmed as the pupils cheered: “Long live the King, long live Saad Zaghloul!” The cheering has changed and so have the songs. Prices have exploded. Behind the closed panes, I can see the River Nile and the trees. Our house is the oldest and smallest one on Nile Street: a dwarf amid modern buildings. The River Nile itself has changed and, like me, it is struggling against loneliness and old age. We share the same predicament: it, too, has lost its glory and grandeur and is now no longer even able to get into a tantrum. And then, so much poverty and so many loved ones departed; so many cars, so many fortunes! A cloudy day with premonitions of rain. On such days, it was fun to go on a trip to the Qanater Gardens. Old friends would get together for a meal of fried chicken, potatoes, and drinks. And the record player playing old favorites. They are all skeletons now and their carefree, mirthful laughter has gone with the wind! They all stood behind me in a row on my wedding night, the night I unveiled Fatma for the first time. Five years have gone by since I last visited your grave. What mad speed and what crowds, the likes of which the trees have never witnessed since they were planted in the days of Khedive Ismail! Madmen rush unawares to meet their fate in accidents. The Prophet, God bless him and grant him salvation, said: “Ye slave of God, be in this world as a stranger or passerby and reckon yourself among the dead.” The Messenger of God has truly spoken.

Elwan Fawwaz Muhtashimi

The beginning of a new day. Old. New, old. New, old. New, old. New, old. Old, new. Dizzying. If there can’t be old that is good, then let there be new that is bad. Anything is better than nothing. Death itself is novelty. Walking is health and a means of economizing. It’s supposed to be the road to love and beauty and look what it is! Ouch, my feet! Ouch, my shoes! Endure and be patient, for this is the age of endurance and having to be patient. In these days of fire and brutes, no breeze to cool the heart but you, my love. Still one must be grateful to the majestic trees and, above all, to the River Nile. Look up above, at the white clouds and the treetops so that you may forget the pockmarked surface of the earth. One day, you’ll meet an innocent devil and befriend him. I bow to the all-powerful mind, to nobility of character and to profound thought.

I have lived in this old house, lost amid towering buildings—an intruder among the rich—since childhood through adolescence and young adulthood. One of these days, the landlord will kill us. Amazing that love should survive amid this ever-spreading corruption. Is this shaky sidewalk the remnant of an air raid? Rubbish heaps lying there in corners guarding lovers. Good morning, you people, piled up in buses, your faces looking out behind cracked glass panes like those of prisoners on visiting days. And the bridge bursting with passersby. Cyclists greedily—but unremittingly—devouring bean sandwiches.

“With every mounting crisis comes relief,” said my grandfather.

Dear Grandpa, till when will we go on learning things off by heart and parroting others? He’s my best friend. And I’m but an orphan. I lost my parents when they lost themselves in continuous work from morning to night, shuttling between the government and private sector to eke out a meager living. We meet only fleetingly.

“No time for idle philosophizing, please. Can’t you see that we can’t even find time for sleep?”

When any of my sisters quarrel with their husbands, I’m the one who’s sent over to try to patch things up! These days, no one finds anyone to help. We all have to struggle, and finally it’s you and your luck! Here now is that food company—one of the public-sector firms—on the entrance of which you can read in bold print: ENTER HERE WITHOUT HOPE. And, finally, there is my sweetheart seated in our office: Public Relations and Translation. She looks at me with a smile suffused with love.

“Had you waited a few minutes, we would’ve come together,” I reprimanded her.

“For reasons I won’t bother you with, I had to have breakfast at the Brazilian Coffee Stores Café,” she answered cheerfully.

Thanks to my grandfather, we were able to be in the same company and in the selfsame division. Rather, it was thanks to one of the Free Officers who had, at one time, been one of his pupils. My grandfather is an unforgettable character so that even those who would normally not acknowledge the good offices of their predecessors would nevertheless have to acknowledge their debt to my grandfather. There are so many women in our division. Piles of paper crowding our work, paperwork that needs no serious effort of concentration. I work a little and then steal a glance at Randa.

I reminisce and dream. I dream and reminisce. A long story going back to the beginning of time in our old house, the only one of its kind. We played together as children. We were the same age. Mama insists—she has no proof—that she is older than I. Puberty comes along and, with it, a certain bashfulness and wariness. My conscience pricks me, dampening all pleasures. But ultimately love got the upper hand. It was during our secondary-school days. On the staircase, midway between both landings, we would indulge in fleeting flirtations and insinuations. One day, I flung a letter of confessions into her hands. In reply, she offered me a novel entitled The Loyalty of Two Generations. When, in the same year, we both passed our secondary-school examinations, I told my grandfather that I wanted to get engaged to our neighbor, Randa Sulayman.

My grandfather told me that, in his day, one was not allowed to talk about an engagement before one became totally independent. But he promised he would open up the subject with Father and Mother. He also promised to give me a hand. My mother said that the family of Sulayman Mubarak was closer to us than our own relatives, and that Randa was just like one of her daughters. “But she is older than you!” My father said, “She’s your age if not a little older and just as poor!”

Our engagement was announced on a happy

day. In those days, a dream could still come true. But the moment we started working we had to face a new set of problems. Three years went by, and we turned twenty-six. I was in love then, but now I am exhausted, helpless, and burdened with responsibilities. We no longer meet just to talk but to engage in endless discussions, enough to allow us to qualify for the Economics Group: the flat, the furniture, the burdens of a life together. Neither she nor I have a solution. We have only love and determination. Our engagement was announced in the Nasser era and we were made to face reality in the days of Infitah. We sank in the whirlpool of a mad world. We are not even eligible for emigration. There is no demand for philosophy or history majors. We are redundant. So many redundant people. How did we get to this point of no return? I am a man persecuted and burdened with responsibilities and doubts; she is pretty and desirable. There I stand, broad as a dam, blocking her path.

Everywhere I see her parents’ angry looks. I can almost hear what is being said behind my back. And over and above that float the dreams of reform. They come from above or from below through resolutions or revolutions! The miracle of science and production! But what of what is being said about corruption and crooks? What Alyaa Samih and Mahmud al-Mahruqi are saying is just awful. What is right? Why have I become suspicious of everything since the fall of my idol in June 1967? How do people find a magic formula for amassing colossal wealth in record time? Could this happen without corruption? What is the secret of my insistence on remaining a man of principles? All I aspire to at this point is to be able to marry Randa.

Randa and I have been asked to meet Anwar Allam, the Chief of Division. We are summoned together since we work together on translating the statutes. He’s a pleasant, gregarious sort of man and loves to show off: slim, tall, and dark, with round eyes and a sharp look. He’s also an old man approaching his fifties and a bachelor.

“Hello, my bride- and bridegroom-to-be!” said Anwar Allam in his usual manner.

He started looking at our work, hurriedly but intelligently making some remarks here and there. As he returned the draft, he inquired, “When is the happy day?”

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma