- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Read online

NAGUIB MAHFOUZ

AKHENATEN

Dweller in Truth

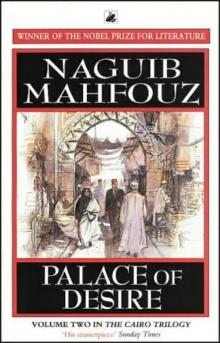

Naguib Mahfouz was born in Cairo in 1911 and began writing when he was seventeen. A student of philosophy and an avid reader, his works range from reimaginings of ancient myths to subtle commentaries on contemporary Egyptian politics and culture. Over a career that lasted more than five decades, he wrote 33 novels, 13 short story anthologies, numerous plays, and 30 screenplays. Of his many works, most famous is The Cairo Trilogy, consisting of Palace Walk (1956), Palace of Desire (1957), and Sugar Street (1957), which focuses on a Cairo family through three generations, from 1917 until 1952. In 1988, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first writer in Arabic to do so. He died in August 2006.

THE FOLLOWING TITLES BY NAGUIB MAHFOUZ ARE

ALSO PUBLISHED BY ANCHOR BOOKS:

The Thief and the Dogs

The Beginning and the End

Wedding Song

The Beggar

Respected Sir

Autumn Quail

The Time and the Place and other stories

The Search

Midaq Alley

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

Miramar

Adrift on the Nile

The Harafish

Arabian Nights and Days

Children of the Alley

Echoes of an Autobiography

The Cairo Trilogy:

Palace Walk

Palace of Desire

Sugar Street

Contents

The Beginning

The High Priest of Amun

Ay

Haremhab

Bek

Tadukhipa

Toto

Tey

Mutnedjmet

Meri-Ra

Mae

Maho

Nakht

Bento

Nefertiti

The Beginning

It all began with a glance, a glance that grew into desire, as the ship pushed its way against the calm, strong current at the end of the flood season. The journey started from our city Sais, heading south toward Panopolis, where my sister had lived since her marriage. One late afternoon, our ship passed a strange city. It was bordered by the Nile to the west, and an imposing mountain to the east. Its buildings hinted of a past grandeur that had given way to a haunting evanescence. The roads were empty, the trees were leafless, the gates and windows closed like eyelids of the dead. A city devoid of life, inert, possessed by silence, shadowed by gloom and the spirit of death. I was dismayed at the sight of it, and I hurried to my father, who was seated, crowned with the dignity of old age, on a bench on the ship's deck.

“Father, what is wrong with this city?”

“Meriamun, this is the city of the heretic. The cursed and infidel city,” he replied calmly.

I looked again with increasing excitement, as the memories flowed.

“Does no one live there?”

“That woman, the heretic's wife, she still lives in her palace—or her prison I should say. And there must be a few guards.”

“Nefertiti,” I murmured to myself, remembering, and wondering how she had endured her isolation.

Visions from my boyhood at my father's palace in Sais kept coming to me, of the elders' fervent debates about the whirlwind that had devastated Egypt and the whole empire. They called it the war of the deities. I remembered the stories about the young pharaoh who had rejected his ancestors' heritage, challenged the priests, and defied destiny. I recalled those hushed voices, the talk of a new religion, and the people's bewilderment, unable to choose between their old faith and their loyalty to the pharaoh. People argued about unusual events, the terrible defeat of the empire, then the triumphs followed by grief.

So here was the city of wonders, possessed by the spirit of death. And there was its mistress, a solitary prisoner sipping bitterness. My heart beat fast, desperate to learn the whole story.

“You will never accuse me of meekness hereafter, Father, for I am swept by a sacred desire, strong as the northern winds, a desire to know the truth and record it, as you did in the prime of your youth.”

He glanced at me with weary eyes and said, “What is it that you want, Meriamun?”

“I want to learn everything about this city and its ruler. About the tragedy that ripped the country apart and laid waste the empire.”

“But you heard everything in the temple,” he replied.

“Father, the sage Qaqimna said, ‘Pass no judgment upon a matter until you have heard all testimonies.’”

“But the truth in this case is evident. Besides, Akhenaten, the heretic, is dead.”

“Most of his contemporaries are alive though,” I replied with growing excitement, “and they are your peers and friends. An introduction from you, Father, would help open doors and reveal secrets to me. Then I could see the many facets of truth before it perishes like this city.”

I insisted until finally he granted me his approval, possibly with concealed enthusiasm. For Father himself had a passion for knowledge and recording the truth, a fact that made our palace a gathering point for men of both worldly and religious affairs. Our palace was famous for its forums where stories were narrated and poetry recited, and for the great banquets of delicious duck and fine wines. Father was known among his friends as a man blessed with unique wisdom and abundant land.

He handed me some letters to deliver to the notable people who remembered that time: those who had participated closely, or from afar, and those who had experienced its bitterness as well as its sweetness.

“You have chosen your path, so walk it. May the gods protect you,” said Father. “Your forefathers sought war, politics, or trade, but you, Meriamun, you seek the truth instead, and one's cause ranks as high as the determination vested in it. Be careful not to provoke the powerful, or gloat over the misfortune of those who have fallen into oblivion. Be like history, impartial and open to every witness. Then deliver a truth that is free of bias for those who wish to contemplate it.”

I was happy to bid indolence farewell, and to set off along the path of history in search of truth, a path that has no beginning and no end, for it will always be extended by those who have a passion for eternal truth.

The High Priest of Amun

Thebes had returned to prosperity after its terrible desertion by the heretic. Once more it was the capital of the empire, its throne graced by the young pharaoh Tutankhamun. Men of peace and war returned to their positions, and the priests resumed their duties in the temples. Palaces were restored, gardens blossomed, and the temple of Amun regained its grandeur and stood proudly with its giant columns and flowering garden. The markets were filled with buyers, merchants, and goods, and the stream of wealth flowed continuously. The city was now a marvel of glory.

It was my first venture to Thebes. I was dazzled by its brilliant architecture and amazed by its vast population. I was overwhelmed by the sounds of the city and the sight of its roads, busy with carriages and carts. In comparison, my city Sais seemed like a small, quiet, obscure village.

I reached the temple of Amun at the appointed time. A servant ushered me through the hall of grand columns and into a lateral corridor leading to the room where the high priest awaited me. I saw him in the center of the room, seated on a chair of ebony with armrests of pure gold. He was an elderly man with a shaved head, and was dressed in a long flowing skirt, with a white sash wrapped around his chest and shoulders. Despite his advanced age he was a man of vigor and had a confident heart. He honored my father at the mention of his name and praised his loyalty.

“Those times of adversity helped us recognize men of good will like your father,” he said. Then he murmu

red a few compliments regarding my endeavor and continued, “We have destroyed the walls with all the false inscriptions they bore. The truth, however, must be recorded.” He leaned his head forward in gratitude. “Now Amun sits prosperously on his throne and in the holy of holies, master of all deities, protecting Egypt and fighting off its enemies. His priests, too, have regained their precedence. Amun liberated our valley by the power he vested in Ahmose, and extended our empire in every direction by the power he vested in Tuthmosis III. For he grants victory to whom he wishes, and humbles those who betray him.”

I knelt in reverence until he called on me to rise and be seated on a chair before him. I listened carefully as the high priest spoke.

It is a very sad story, Meriamun, though in the beginning it seemed merely an innocent whisper. It started with the Great Queen Tiye, the heretic's mother and wife of the Great Pharaoh, Amenhotep III. She came from a common Nubian family, with not a drop of royal blood in her veins. Yet she was shrewd and powerful, as though she had four eyes and could see in all directions at once. She was intent on maintaining friendly relations with us. I shall never forget her words on the day of the Nile Festival: “You priests of Amun are the fortune and blessing of Egypt.” She was so strong that she could stare with her beautiful, big eyes into the faces of powerful men till they lowered their gaze in embarrassment. We, however, did not regard her with apprehension, for we knew how the pharaohs of this glorious family had always cherished and supported the priests of Amun. Then the queen declared an interest in broadening the scope of theological doctrine to encompass other deities, and in particular Aten. On one level it appeared as a mere expansion in the knowledge of religions that we all respected and held sacred. There was no sense in protesting, although we were displeased that other deities should attain such merit here in Thebes, the home of Amun. Tiye assured us that Amun would forever remain the master of all deities, and that his priests would rank above all others in Egypt. But her words did not appease us.

One day Toto, the chanter priest, said to me, “I detect behind the queen's decision a new policy that has nothing to do with religion.” When I queried his statement, he continued, “The Great Queen is seeking the sympathy of the provincial priesthood in order to curb us, limit our power, and strengthen that of the sovereign.”

“But we are the servants of Amun, and in the service of the people. We are the teachers, the healers, and the guides in this world and the hereafter. The queen is a wise woman; she must acknowledge our merits,” I replied.

“But this is a power struggle. The queen is ambitious. In my opinion she is more powerful than the king,” he said irritably.

“But we are the sons of the greatest deity. We are backed by a heritage stronger than destiny,” I argued, against my own misgivings.

Maybe at this point I should tell you about King Amenhotep III. His grandfather, Tuthmosis III, had established an empire that surpassed all others in its vastness and the multitude of its peoples. Amenhotep III was a powerful king. He rose to the defense of his country at the slightest alarm, and achieved such triumphs that the whole empire gave him allegiance. Peace and wealth prevailed throughout his long reign, and he cultivated the fruit of his forefathers' work. Crops, minerals, fabrics, and goods, everything was abundant in Egypt. He built beautiful palaces, temples, and sculptures. He indulged himself in fine food, wine, and women, but his wife Tiye knew his strengths and weaknesses, and used them to good effect. She encouraged him to fight at times of war, and tolerated his philandering, sacrificing her feminine emotions in order to share his throne and pursue her boundless ambition. I do not deny her the merit of knowing every detail of the empire's affairs. Nor do I question her loyalty and farsightedness, or her concern for the glory of Egypt. But I do condemn her greed for power. It was greed that tempted her to exploit religion to attain exclusive power for the throne, and marginalize the priests. Gradually I became aware of other ideas that occupied her mind. One day she came to the temple, and after making her offering to Amun, preceded me with firm stride to the reception hall. As soon as we were seated she asked, “What is it that worries you?”

Before I could think of an answer, she continued quickly. “Like the priests I can read what is buried deep in people's hearts. You suspect that I have raised the status of other priests to the disadvantage of the priests of Amun.”

“The priests of Amun are loyal subjects of your glorious family,” I replied.

“Here is what I think,” she said, her eyes glaring as she continued. “Amun is the master of all deities in Egypt. For our citizens in the empire, he is a symbol of power. They fear him. But Aten shines for everyone. He is the sun god, and anyone can embrace him.”

I wondered if she was sincere, or whether it was just another pretense masking her desire to neutralize our power. In any case, I was not convinced by the argument itself.

“Your Highness,” I said, “those savages must be ruled by force, not compassion.”

“By compassion, too,” she replied with a smile. “What is appropriate for a wild beast is not always suitable for the tamed animal.”

This seemed to me a futile, womanish concept that might very well have disastrous consequences. And I was proven right by the painful events that followed.

The high priest was silent for a while as he gathered his thoughts. Then he continued.

At the beginning of her marriage, Tiye faced some difficulties. She remained childless for a considerable time, and feared she might be barren, particularly since she came from a common family. But, by the virtue of Amun and his priests, our good prayers and effective sorcery, the queen became pregnant. Even then, she gave birth to a girl. Whenever I met her in the palace or the temple, she would look at me with wariness and suspicion, as though I was responsible for her misfortune. We would never have thought of disturbing the order of the throne. It was the queen's own wickedness that made her so distrustful.

Once more he was silent, as though reluctant to continue. Then he said, “Then, in some mysterious way, she bore two sons.” He thought a while, setting my curious soul on fire. “The older and better of the two passed away, while the other remained to exercise his perversity in the destruction of Egypt.” I said nothing, but the high priest noticed my eagerness and went on.

We have ways of hunting out the truth even when it is hidden from others. We have the power of sorcery, and our eyes are everywhere in the empire. The heretic was a man of questionable birth, effeminate and grotesque. Following in the footsteps of his father, Amenhotep III, he married a common girl. Nefertiti was like his mother, not only in humble descent, but also in her insatiable ambition and lust. She was beautiful, stubborn, and defiant. She plunged into the affairs of the country, supporting her husband's destructive policy. She bore six girls, the fruit of her liaisons with other men. Despite his apparent love for Nefertiti, Akhenaten never really loved anyone but his mother, who gave him life and nurtured his absurd ideas. He sensed Tiye's pain and loneliness, and harbored rage against his father. When Amenhotep III died, Akhenaten erased his name from all the monuments. He said he meant to erase the name of Amun from the people's memory, and to do that his father's name—Amenhotep, meaning Amun is Content—had also to be erased. The truth is, having failed to avenge himself during his father's life, he killed him after his death. When Tiye taught him the religion of Aten, it was merely a political maneuver. But the boy believed in it as an end in itself. Politics did not befit his feminine nature. What happened next was something even his mother had not anticipated. He became a heretic.

I still remember his repulsive appearance, neither man nor woman. Because he was so weak and frail, he naturally became resentful of all strong men, priests, and deities. He conceived of a god similar to himself in weakness and femininity, both father and mother, with no other purpose but love. A god worshiped with rituals of dance and song! Akhenaten drowned in a swamp of foolishness, and neglected his obligations to the throne, while our men and loyal allies wer

e being massacred by the enemies of the empire. Though they cried for help, they received none, and eventually the empire was lost, Egypt was destroyed, the temples were empty, and the people famished. That was the heretic who called himself Akhenaten.

Overwhelmed by the intensity of his memories, the high priest was silent for a while. I waited patiently, until at last he laced his fingers and rested his hands in his lap.

I first received reports about Akhenaten when he was still a young boy. I had my eyes in the palace, men who had dedicated themselves to the service of Amun and the country. They told me that the crown prince nurtured a suspicious affinity for Aten, favoring him over Amun, master of all deities. I learned that every day at dawn the boy went to a secluded spot on the Nile bank to greet the sunrise in solitude. I foresaw in his strange practices a future laden with trouble. I went to the palace, where I confessed my fears to the king and queen.

“My son is still young,” Amenhotep III smiled.

“But the young boy will grow, and he will retain within him the ideas of his childhood.”

“He is but an innocent child seeking wisdom wherever he thinks he might find it,” Tiye said.

“Soon he will begin his military training and learn his true calling,” the pharaoh added.

“We have no need of more countries to add to our empire. What we need is the wisdom to keep what we already have,” Tiye said.

“My glorious Queen,” I argued, “the safety of the empire relies on the blessings of Amun and the exercise of power.”

“I am surprised that a wise man like yourself should undervalue the role of wisdom in such a manner,” said the cunning queen.

“I do not deny the importance of wisdom,” I insisted, “but without power, wisdom is nothing but chatter.”

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma