- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens Read online

Naguib Mahfouz

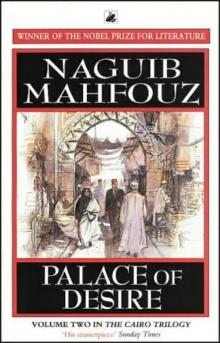

Naguib Mahfouz was born in Cairo in 1911 and began writing when he was seventeen. A student of philosophy and an avid reader, his works range from reimaginings of ancient myths to subtle commentaries on contemporary Egyptian politics and culture. Over a career that lasted more than five decades, he wrote thirty-three novels, thirteen short story anthologies, numerous plays, and thirty screenplays. Of his many works, most famous is The Cairo Trilogy, consisting of Palace Walk (1956), Palace of Desire (1957), and Sugar Street (1957). In 1988, he became the first writer in Arabic to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He died in 2006.

BOOKS BY NAGUIB MAHFOUZ

The Beggar, The Thief and the Dogs, Autumn Quail (omnibus edition)

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, The Search (omnibus edition)

The Beginning and the End

The Time and the Place and Other Stories

Midaq Alley

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

Miramar

Adrift on the Nile

The Harafish

Arabian Nights and Days

Children of the Alley

Echoes of an Autobiography

The Day the Leader Was Killed

Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth

Voices from the Other World

Khufu’s Wisdom

Rhadopis of Nubia

Thebes of War

Seventh Heaven

The Thief and the Dogs

Karnak Café

Morning and Evening Talk

The Dreams Cairo Modern

Khan al-Khalili

The Mirage

THE CAIRO TRILOGY:

Palace Walk

Palace of Desire

Sugar Street

The Mummy Awakens

from Voices from the Other World

Naguib Mahfouz

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Penguin Random House LLC

New York

Copyright © 1945 by Naguib Mahfouz

English translation copyright © 2002 by Raymond Stock

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House of Canada Ltd., Toronto. Originally published in hardcover as part of Voices from the Other World in the United States by The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo and New York, in 2003.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for Voices from the Other World is available from the Library of Congress.

Vintage eShort ISBN 9781101973417

Series cover design by Joan Wong

www.vintagebooks.com

v4.1

a

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Books by Naguib Mahfouz

Title Page

Copyright

The Mummy Awakens

I am deeply embarrassed to tell this tale—for some of its events violate the laws of reason and of nature altogether. If this were merely fiction, then it would not cause me to feel such embarrassment. Yet it happened in the realm of reality—and its victim was one of the most renowned and extraordinary men of Egypt’s political and aristocratic circles. Moreover, I am relating it as recorded by a great professor in the national university. There is no room for doubt of his sentience or his character, nor is he known for any tendency toward delusions or wild stories. Still, it may truly be said, I do not know how to believe it myself, nor to persuade others to do so. This is not due to the want of miracles and wonders in our time. Yet rational people of our day do not accept matters without good cause—just as they do not oppose putting faith in something if there is a logical explanation for it. Though the strange account that I now transmit has claims of authenticity, a coherent narrative, and tangible attestations, the scientific basis for it is still much in doubt. Would I not, then, express my hesitation in presenting it?

Whatever one makes of the matter, here it is as portrayed by Dr. Dorian, professor of Ancient Egyptian Archaeology at Fuad I University:

On that painful day, when the heart of Egypt shook with anguish and sorrow, I went to visit the late Mahmoud Pasha al-Arna’uti at his grand country palace in Upper Egypt. I remember that I found the Pasha with a group of friends that flocked around him when circumstances permitted. Among them was M. Saroux, headmaster at the school of fine arts, and Dr. Pierre, the expert on mental diseases. We all gathered in his elegant, sophisticated salon, filled with the choicest examples of contemporary art—both paintings and sculpture. It was as though they were marshaled in that place in order to convey the salute of the genius of modernity to the memory of the immortal Pharaonic spark. Buried in the ruins of the Nile Valley, its light nonetheless burned through the darkness of the years like the points of the harmonious stars in the sky, a voyager through the void of the jet-black night.

The deceased was among the richest, most cultured people in Egypt, and the noblest in disposition. His friend Professor Lampere once said of him that he was “three persons in one”—for he was Turkish in race, Egyptian in nationality, and French in his heart and mind. To achieve his acquaintance was the height of accomplishment.

In fact, the Pasha was France’s greatest friend in the East—he thought of her as his second country. His happiest days were those that he spent beneath her skies. All of his companions were drawn from her children, whether they lived on the banks of the Nile or the Seine. I myself used to imagine, when I was in his salon, that I had suddenly been transported to Paris—the French furniture, the French people present, the French language spoken, and the French cuisine. Many French intellectuals did not know him except as a singular fancier of French art, or as a composer of passionate verse in the fine Gallic tongue. As for me, I knew him only this way—as a lover of France, a fanatic for her culture, and a preacher of her policies.

On that fateful day, I was sitting at the Pasha’s side when M. Saroux said, while scrutinizing a two-inch bronze bust with his crossed and bulging eyes, “You fortunate man, your palace needs but a trifling change to turn it into a complete museum.”

“I certainly agree,” the doctor ventured, tugging at his beard contemplatively, “for it is a permanent exhibit of all the schools of genius combined, with an obvious Francophile tendency.”

The Pasha chimed in, “Its greatest virtue is in my balanced taste, which moves equally between the various trends, treating the rigid views of the differing schools all the same. And which strives for the enjoyment of beauty—whether its creator be Praxiteles or Raphael or Cézanne—with the exception of radical modern contrivances.”

As I spoke, I glanced covertly at M. Saroux, teasing whom always delighted me, and said, “If the Ministry of Education could move this salon to the Higher College of Fine Arts, then they wouldn’t waste money sending study missions to France and Italy.”

M. Saroux laughed, swiveling to address me, “Then maybe they could save on the French headmaster, as well!”

But the Pasha said seriously, “Be assured, my dear Saroux, that if it were possible for this museum to leave Upper Egypt, then it would be heading straight for Paris.”

We stared at him with surprise, as if we did not believe our ears. In truth, the Pasha’s art collection was worth hundreds of thousands of Egyptian pounds—all of which had flowed into French pockets. It was stunning that he would think of donating it to France. While we were entitled to rejoice and be glad at this idea, nonetheless I could not restrain myself from asking:

“Excellence, is what you are saying true?”

The Pasha answered

calmly, “Yes, my friend Dorian—and why not?”

M. Saroux broke in, “How deservedly happy and jubilant we French should be! But I must tell your Excellency sincerely that I fear this may bring you a great many troubles.”

When I seconded M. Saroux’s view, the Pasha shifted his blue eyes back and forth between us with a sarcastic expression, and asked in feigned ignorance, “But why?”

Without hesitation, I said, “The press would find that quite a subject!”

“There is no doubt that the nationalist press is your old enemy,” said Dr. Pierre. “Have you forgotten, Your Excellency, their biased attacks against you, and their accusations that you squander the money of the Egyptian peasants in France without any accountability?”

The Pasha sighed in dismissal, “The money of the peasants!”

Apologetically, the doctor hastened to add, “Please forgive me, Pasha—this is what they say.”

Pursing his lips, His Excellency shrugged his shoulders disdainfully, as he adjusted his gold-rimmed spectacles over his eyes, saying, “I pay no heed to these vulgar voices of denunciation. And so long as my artistic conscience is ill at ease with leaving these miracles amidst this bestial people, then I will not permit them to be entombed here forever.”

I knew my friend the Pasha’s opinion of the Egyptians and his contempt for them. It is said in this regard that the year before, a gifted Egyptian physician, who had attained the title of “Bey,” came to him, asking for the hand of his daughter. The Pasha threw him out brutally, calling him “the peasant son of a peasant.” Despite my concordance with many of the Pasha’s charges against his countrymen, I could not follow his thinking to its end.

“Your Excellency is a very harsh critic,” I told him.

The Pasha giggled, “You, my dear Dorian, are a man who has given his entire, precious life to the past. Perhaps in its gloom you caught the flash of the genius that inspired the ancients, and it has inflamed your sympathy and affection for their descendants. You must not forget, my friend, that the Egyptians are the people who eat broad beans.”

Laughing too, I bantered back, “I’m sorry, Your Excellency, but do you not know that Sir Mackenzie, professor of English language at the Faculty of Arts, has recently declared that he has come to prefer broad beans to pudding?”

The Pasha laughed again, and so did we all with him. Then His Excellency said, “You know what I mean, but you like to jest. The Egyptians are genial animals, submissive in nature, of an obedient disposition. They have lived as slaves on the crumbs from their rulers’ banquets for thousands of years. The likes of these have no right to be upset if I donate this museum to Paris.”

“We are not speaking about what is right or not right, but about reality—and the reality is that they would be upset about it,” said Saroux. “And their newspapers will be upset about it along with them,” he added, in a meaningful tone.

Yet the Pasha displayed not the slightest concern. He was by nature scornful of the outcry of the masses, and the deceitful screams of the press. Perhaps due to his Turkish origins, he had the great defect of clinging to his own conceptions, his pertinacity, and his condescension toward Egyptians. He did not want to prolong the discussion, but closed the door upon it with his rare sense of subtlety. He kept us occupied for an hour sipping his delicious French coffee—there was none better in Egypt. Then the Pasha peered at me with interest, “Are you not aware, M. Dorian, that I have begun to compete with you in the discovery of hidden treasures?”

I looked at him quizzically and asked, “What are you saying, Excellence?”

The Pasha, laughing, pointed outdoors through the salon’s window, “Just a short distance from us, in my palace garden, there is a magnificent excavation in progress.”

Our interest was immediately obvious. I expected to hear a momentous announcement, for the word “excavation” prompts a special stimulus in me. I have spent an enormous part of my life—before I took up my post at the university—digging and sifting through the rich, magical earth of Egypt.

Still smiling, the Pasha continued, “I hope that you will not all make fun of me, my dear sirs, for I have done what the ancient kings used to do with sorcerers and masters of legerdemain. I don’t know how I yielded to it, but there is no cause for regret, for a bit of superstition relieves the mind of the weight of facts and rigorous science. The gist of the story is this. Two days ago, a man well known in this area, named Shaykh Jadallah—whom the people here respect and revere as a saint (and how many such saints do we have in Egypt!)—came to me, to insist on a peculiar request. And I acceded to it, amazing as it was.

“The man hailed me, in his own manner, and informed me that he had located—by means of his spiritual knowledge and through ancient books—a priceless treasure in the heart of my garden. He beseeched me to let him uncover it, under my supervision, tempting me with gold and pearls, if I would but gratify his wish. He was so annoying that I considered tossing him out. But he begged and pleaded with me until he wept, saying: ‘Do not mock the science of God, and do not insult his favored believers!’ I laughed a long time—until I had a sudden thought, and said to myself, ‘Why don’t I humor the man in his fantasy and go along with him in his belief? I wouldn’t lose anything, and I would gain a certain type of amusement.’ And so I did, my friends, and gave the man my permission.

“And now, in all seriousness I show him to you—he who is digging in my garden, with two of my faithful servants assisting in his arduous labor. What do you think?”

The Pasha said all this with considerable mirth: we all laughed again with him. But as for myself, I recalled an incident similar to this one: “Naturally, you don’t believe in the science of Shaykh Jadallah. Nor can I believe in it, either—more’s the pity. But I also cannot forget that I discovered the tomb of the High Priest Kameni because of this same superstition!”

The amazement was plain on the faces of those present, and the Pasha queried me, “Professor, is what you are saying true?”

“Yes, Pasha, one day a shaykh like Shaykh Jadallah came to me in a place near the Valley of the Kings. He said that he had found, by means of his books and knowledge, the whereabouts of a treasure there. We kept pounding away in that spot, and—before the day was out—we found Kameni’s tomb. This was, without a doubt, one of the most brilliant of coincidences.”

Dr. Pierre laughed ironically, “Why do you credit that to coincidence, and deny the ancient science? Isn’t it conceivable that the pharaohs bequeathed to their descendants their hidden secrets, just as they passed on to them their appearance and their customs?”

We kept on distracting ourselves with this sort of chatter, flitting from one topic to another, passing the time in great pleasure. And just before sunset, the guests took their leave. But I announced my wish to observe the excavation that Shaykh Jadallah was conducting in the garden. So we all left the salon, walking through the rear door to bid our good-byes. We had gone but a few steps when we could hear the sounds of a great uproar—and a group of the servants cut across our path. We saw that they were holding a Sa‘idi man, an Upper Egyptian, by his collar, giving him a sound beating with their fists. They dragged him roughly up to the Pasha, and one of them said, “Your Excellency, we caught this thief stealing Beamish’s food.”

I knew Beamish quite well—he was the Pasha’s beloved dog, the most precious creature of God to his heart after his wife and children. He lived a spoiled and honored life in the Pasha’s palace—attended by the staff and servants, and visited by a veterinarian once every month. Each day he was presented with meat, bones, milk, and broth—this wasn’t the first time that the Sa‘idis had pounced on Beamish’s lunch.

The thief was an unmixed Upper Egyptian, marked by the looks of the ancients themselves. It was clear from his dress that he was wretchedly poor. The Pasha fixed him with a vicious stare, interrogating him gruffly, “Whatever induced you to violate the sanctity of my home?”

The man replied in fervent entreaty,

panting from his efforts to fight off the servants, “I was starving, Your Excellency, when I saw the cooked meat scattered on the grass. My resistance failed me—I haven’t tasted meat since the Feast of the Sacrifice!”

Turning to me, the Pasha exclaimed, “Do you see the difference between your unfortunates and ours? Your poor are propelled by hunger into stealing baguettes, while ours will settle for nothing less than cooked meat.”

Then, raising his cane in the air, he wheeled back upon the thief and struck him hard on the shoulder, shouting to the servants, “Take him to the watchman!”

As the man was handed over, Dr. Pierre laughed, inquiring of the Pasha, “What will you do tomorrow if the natives get a whiff of the heaps of gold in the treasure of Shaykh Jadallah?”

The Pasha replied instantly, “I’ll surround it with a wall of sentries, like the Maginot Line!”

We—the Pasha and I—bade the others farewell, and I followed him silently to where Shaykh Jadallah seemed about to transform himself into a great archaeologist. He was a man completely absorbed in his work—he and his helpers alike. They hacked at the earth with their hoes, lifting the dirt with baskets and throwing it aside. Shaykh Jadallah—his eyes flashing with a sharp gleam of hope and resolve, his scrawny arms charged with an unnatural strength—was nearing his goal, to which his divine insight had guided him. To me, his anomalous person represented Man in his activity, in his belief, and in his illusions—for the truth is that we create for ourselves gods and hallucinations, yet we believe in them in an extraordinary fashion. Our belief makes worlds for us of extreme beauty and creativity. Did not the ancestors of Shaykh Jadallah—whose face reminds me of the famous statue of an ancient Egyptian scribe—make humanity’s first civilization? Did they not create loveliness equally on the surface of the earth, and beneath it? Were they not inspired in their work and their thought by Osiris and Amon? And what is Osiris, and what is Amon? Nothing much, on the whole. As for their civilization, it could be compared with—indeed, it is—our own civilization today.

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma