- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Page 2

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Read online

Page 2

“In this palace,” the pharaoh interjected, “there is no question that Amun is the master of all deities.”

“But the prince has stopped visiting the temple,” I said anxiously.

“Be patient,” the king replied. “Soon my son will fulfill all his obligations as crown prince.”

I returned from the palace with no solace. Indeed, after hearing the king and queen come to the prince's defense, my fears were even stronger. Then I heard about a conversation the crown prince had with his parents and I became convinced that within the prince's frail body was an abyss of evil power. One day one of my men asked to see me. “Even the sun is no longer a god,” he said. I queried him and he continued, “There are rumors that a new god has revealed himself to the crown prince, claiming to be the one and only true god and that all other deities are spurious.”

The news stunned me. The fate of the older brother who died was more merciful than the madness that had descended upon the crown prince. The tragedy had reached its climax.

“Are you certain of what you say?”

“I am merely reporting what everyone says.”

“How did this so-called god reveal himself to the prince?”

“He heard his voice.”

“No sun? No star? No idols?”

“Nothing at all.”

“How can he worship what he cannot see?”

“He believes that his god is the only power capable of creation.”

“He has lost his mind.”

The chanter priest, Toto, said, “The prince has gone mad and is no longer fit to take the throne when the time comes.”

“Quiet,” I said. “That the prince is an infidel does not change the fact that Amun and our gods will remain the only deities worshiped by the people in the empire.”

“How can a heretic take the throne and rule the empire?” Toto asked angrily.

“Let us not be hasty. We will wait until the truth is clear, then we will discuss the matter with the king,” I continued, my heart heavy with gloom. “It will be the first confrontation of its kind in history.”

When the crown prince married Nefertiti, the eldest daughter of the sage Ay, I held by the last of all hopes— that in marriage, the prince would return to his senses. I summoned Ay to the temple. As we talked, it became clear to me that the sage was extremely cautious in what he said. He was certainly in a predicament, and I sympathized with him, saying nothing about the prince's unbelief. Before he left, I asked him to arrange for me a private conference with his daughter.

Nefertiti arrived promptly. I looked at her keenly, and saw beyond her captivating beauty a roaring torrent of strength and power. I was instantly reminded of the Great Queen Tiye, and hoped this power would work with us and not against us.

“I grant you my blessing, my daughter.”

She expressed her gratitude in a sweet, pleasing voice.

“I have no doubt that you are fully aware of your duties as the wife of the crown prince. But it is also my duty to remind you that the throne of the empire is founded on three fundamentals: Amun, the master of all deities; the pharaoh; and the queen.”

“Indeed. I am fortunate to be granted the honor of your wisdom.”

“A sensible queen must bear with the king the burden of protecting the empire.”

“Dear Holy Priest,” she said firmly, “my heart is filled with love and loyalty.”

“Egypt is a country of timeless traditions, and women are the sacred guardians of this heritage.”

“Duty, too, dwells within me.”

Nefertiti remained wary and reserved throughout her visit. She spoke, but revealed nothing. She was like a mysterious carving with no inscription to explain it. I could extract no information from her words, nor could I express my fears directly. Yet her wariness meant that she knew everything and that she was not on our side. Her position did not surprise me in the least. By a stroke of luck capable of turning the strongest head in the country Nefertiti had found herself a future queen. Her primary concern was neither Amun nor indeed any of the deities—she craved only the power of the throne. I said a prayer of mourning with the other priests in the holy of holies, then related to them the proceedings of my meeting with Nefertiti.

“Soon there will be nothing but darkness,” said Toto the chanter. When all the other priests had left, Toto said, “Perhaps you can discuss the matter with Chief Commander Mae.”

“Toto,” I replied earnestly, recognizing the danger in his allusion, “we cannot defy King Amenhotep III and the Great Queen Tiye.”

Meanwhile in the palace, tension was rising between the mad prince and his parents. Thus King Amenhotep III issued an imperial mandate ordering the crown prince to tour the vast empire. Perhaps the pharaoh had hoped that when the prince became acquainted with his country and subjects he would see the reality of things and realize how far he had strayed from the right path. I was grateful for the king's attempt, but my deep fears continued to haunt me. Then, while the prince was still away, some grave events took place. First, Queen Tiye gave birth to twins, Smenkhkare and Tutankhamun. Shortly after, the pharaoh's health deteriorated, and he died. Messengers from the palace carried the news to the prince, for him to return and take the throne.

I discussed the future of the country with the priests of Amun, and we came to an agreement. Immediately I took action, and asked to meet the queen despite the mourning and her preoccupation with mummifying her husband's body. Even in her grief, the queen was powerful and enduring. I was determined to speak out at any cost.

“My Queen, I came to speak my mind to the rightful matriarch of the empire.” I could tell by the way she looked at me that she knew what I was about to say.

“My gracious Queen, it is well known now that the crown prince does not respect our deities.”

“Do not believe everything you hear,” she replied.

“I am prepared to believe all that you say, Your Majesty,” I said readily.

“He is a poet,” she said. I was not satisfied with her answer but remained silent until she added, firmly, “He will fulfill all his duties.”

I mustered up all the courage I had within me and said, “My Queen is surely aware of the consequences that would befall the throne if the gods were offended.”

“Your fears are unfounded,” she replied irritably.

“If necessity calls we can entrust the throne to one of your younger sons; you will be the guardian regent.”

“Amenhotep IV will rule the empire. He is the crown prince.”

Thus did the wise queen yield to the mother and lover in her. She wasted the last chance for reparation, and armed destiny with the weapon that dealt us a fatal blow. The mad, effeminate crown prince returned in time for the royal entombment.

Soon afterward, I was summoned to appear before him in his formal capacity as the future pharaoh. It was the first time I had seen him closely. He was rather dark, with dreamy eyes and a thin, frail figure, noticeably feminine. His features were grotesque and disturbing. He was a despicable creature, unworthy of the throne, so weak he could not challenge an insect, let alone the Master Deity. I was disgusted but revealed nothing; instead I called to mind the words of wise men and great poets, words that inspired me to keep my patience. He fixed his gaze on me, a look neither hostile nor friendly.

I was so distracted by his appearance that I could not utter a word.

“I have had so many tedious arguments with my parents because of you,” he began.

I was finally able to speak. “My only concern in this life,” I said, “is the service of Amun, the throne, and the empire.”

“You have something to tell me, no doubt,” he said.

“My King,” I replied, anticipating a battle, “I heard disturbing news, but I did not believe it.”

“What you heard is the truth,” he said, seemingly quite unconcerned. I was startled, but he continued, “I am the only man of faith in this heathen country.”

“I cannot believe what I hear.�

��

“You must believe it. There is no god but the One and Only God.”

“Amun will not forgive this blasphemy.” I was so enraged that I no longer cared about the consequences of what I said; my only concern was to defend Amun and our deities.

“No one but the One and Only God can grant forgiveness,” he replied, smiling.

“Nonsense!” I said, shuddering with anger.

“He is the whole meaning of this world. He is the creator. He is the power. He is love, peace, and happiness.” Then he threw me a piercing look that seemed out of keeping with his fragile appearance, and continued, “I call upon you to believe in him.”

“Beware of the wrath of Amun,” I said furiously. “He creates, and He destroys. He grants and dispossesses, aids and forsakes. Fear his vengeance for it shall haunt you to your last descendant, and destroy your throne and the empire.”

“I am but a child in the vast expanse of the One and Only, a budding flower in his garden, and a servant at his command. He granted me his gracious love and revealed himself to my soul. He filled me with brilliant light and beautiful music. That is all that matters to me.”

“A prince does not become a pharaoh until he is crowned in the temple of Amun.”

“I shall be crowned in the open land under the sunlight, with the blessing of the creator.”

We parted on the poorest terms. On my side there was Amun and his followers. Akhenaten had the heritage of his great family, the holiness with which the subjects regarded their pharaohs, and his madness. I prepared myself for holy war, and was ready to sacrifice everything for the sake of Amun and my country. I put myself to work without delay.

“The new pharaoh is a heretic,” I told the priests. “You must know that, and let everyone in the country be informed.”

I too was furious, but I thought it best to channel Toto's anger. I proposed that he should pretend to join the heretic, to become our eyes in the palace. As for the king, he, too, lost no time. He was crowned with the blessings of his so-called god. He even built a temple for him in Thebes, the city of Amun. He proclaimed his new religion to the candidates for his chamber, and consequently the finest men of Egypt declared their faith in the new god. Their particular motives may have varied, but the goal was one—to fulfill their ambition and attain power. Perhaps if they had renounced his religion, things would have taken a different course. But they sold themselves like whores. Take the sage Ay, for instance. He thought himself a part of the pharaoh's family and was blinded by glory. Haremhab, a courageous warrior, was another one. He was a man of no true faith; for him it was simply a matter of substituting one name for another. All the others, too, they were nothing but a band of hypocrites, hungry for wealth and power. Had they not renounced their sinful ways and repented at the critical moment, they would have deserved to die. In the event, they won their lives back, but I have no respect for any of them.

The conflict threatened Thebes. People were torn between their loyalty to Amun and their obligation to the mad offshoot of the greatest family in our history. The Great Queen Tiye was consumed with worry as she watched the seed she had sown grow into a poisonous plant. He was falling into a bottomless pit, dragging his family along with him. Tiye kept bringing her offerings to the temple of Amun, in an attempt to diminish the turmoil that jeopardized the throne.

“You win by allegiance, and lose by defiance,” she said.

“You are asking us to be loyal to a heretic. If only you had listened to me in the beginning.”

“We must not despair.”

Her usual strength collapsed in the face of his mysterious insanity, and she was impotent before her effeminate, spoilt son. It was inevitable that we continue our holy struggle. The mad king was no longer able to bear the pressure in Thebes, particularly when he heard the hostile cries of the people during the feast of Amun. Claiming that his god had commanded him to leave Thebes and build a new city, he left in a grand exodus with eighty thousand other heretics, to live in their accursed exile. His move from Thebes gave us time to prepare for holy war, and allowed him to indulge his blasphemy and make the new capital a place for riotous festivities and orgies. Love and Joy, this was the slogan of his new, nameless god. Whenever his natural weakness stung him, he went to extremes to prove that his power had no limits. The priests were evicted and the temples closed. The idols and all the patrimonial endowments were confiscated. I said to the priests, “It is death and the hereafter you must cherish, for there is nothing to live for now that the temples are closed.” But we found refuge in the homes of the pious followers of Amun. They were our fighters, and we continued the struggle with hope and determination.

The heretic continued to flaunt his power, parading in the provinces and calling upon the people to join him in his heresy. Those were the darkest days. The people were torn and dismayed, not knowing whether to choose their deities or their feeble king and his obscenely beautiful wife. Those were the days of grief and torment, hypocrisy and regret, and fear of divine wrath. But the words of love and joy began to take their toll. The public servants cared little for their duties and exploited citizens for their pleasure. Rebellion spread throughout the empire. Our enemies feared us no more, and began to threaten our borders. When the rulers in the provinces called for help they received poems instead of troops. They died as martyrs, cursing the treacherous heretic with their final breath. The stream of riches that had flown into Egypt from all over the world dried up, leaving the markets bare, the merchants impoverished, and the country famished. I cried out to the people, “The curse of Amun has descended upon us. We must destroy the heretic, or else we will be extinguished in war.”

Still I opted for the path of peace to spare the country the trauma of war. I confronted the queen mother, Tiye.

“I am troubled and grieved, High Priest of Amun,” she said.

“I am no longer high priest.” Bitterness grasped me.

“I am only a hunted vagabond now.”

“I ask the gods for mercy,” she stuttered.

“You must do something. He is your son; he adores you. You are responsible for all that has happened. Caution him before a civil war wipes out everything.”

She was vexed when I reminded her of her responsibility. She said, “I have decided to go to the new capital, Akhetaten.”

Indeed Queen Tiye made some deserving efforts, but she could not repair the damage. I did not despair, but went to Akhetaten, despite the danger in such an undertaking. There I met with the heretic's men.

“I speak to you from a position of power,” I said. “My men are awaiting a signal from me to pounce on you. I am here now in a last attempt to save what can possibly be saved without bloodshed or destruction. I will leave you to yourselves for a while, and trust you will come to your senses and do your duty.”

They appeared to be convinced, and in due time they did what I asked of them, each for his own purposes. But the country was spared grave affliction. They met with the heretic and presented him with two urgent demands—to declare freedom of worship, and to send an army to defend the empire against our enemies who were making incursions across the borders. The mad king refused. They proposed that if he abdicated the throne, he could keep his faith and preach it however he wished. Again, their offer was rejected. But this time he appointed his brother Smenkhkare to share the throne. We disregarded his order and named Tutankhamun king of the throne. The heretic's men deserted him and pledged allegiance to the new pharaoh. In time, order was restored in the country without war or destruction.

We relinquished all desire for revenge on the madman and his wife and those who remained loyal to him.

Amun's followers hurried to the temples after their long deprivation. The nightmare had ended and life began to resume its normal course. As for the heretic, when madness had consumed him, he fell ill and died, disappointed in his god and hopeless of the hereafter. He left behind him his wicked wife to endure loneliness and regret.

The high pri

est gazed at me silently for a long while. Then he said, “We are still healing. We need time and serious effort. Our loss, inside and outside the empire, was beyond estimate. How did it all happen? How could such a mad, distorted person stir up such agony?” He paused for a moment then concluded, “That is the true story. Record it faithfully. Do carry my sincere greetings to your dear father.”

Ay

y was the sage and former counselor to Akhenaten, and father of Nefertiti and Mutnedjmet. Old age had settled in the furrows of his face. I met him in his palace overlooking the Nile in south Thebes. He told me the story in a serene voice without letting his face reveal any emotion. I was in awe of his solemnity and dignity, and the richness of his experience. “Life, Meriamun, is a wonder,” he began. “It is a sky laden with clouds of contradictions.” He contemplated a while, surrendering to a current of memories. Then, he continued.

The story begins one summer day when I was summoned to appear before King Amenhotep III and Great Queen Tiye.

“You are a wise man, Ay,” the queen said. “Your knowledge of the secular and the spiritual is unrivaled. We have decided to entrust you with the education of our sons Tuthmosis and Amenhotep.”

I bowed my shaven head in gratitude and said, “Fortunate is he who will have the honor of serving the king and queen.”

Tuthmosis was seven years old, Amenhotep was six. Tuthmosis was strong, handsome, and well built, though not particularly tall. Amenhotep was dark, tall, and slender, with small, feminine features. He had a tender yet penetrating look that made a deep impression on me. The handsome lad died and the weak one was spared. The death of his brother shook Amenhotep and he wept for a long time.

One day he said to me, “Master, my brother was pious, he frequented the temple of Amun, received his charms and fetishes, but still he was left to die. Master and Sage, why don't you bring him back to life?”

“Son,” I replied, “one's soul is immortal. Let that be your solace.”

That was the beginning of our many discussions on life and death. I was sincerely pleased with his insight and understanding in spiritual matters. The boy was clearly ahead of his years. I often found myself thinking that Akhenaten was born with some otherworldly wisdom. Even in secular subjects, he quickly mastered the skills of reading, writing, and algebra. I said to Queen Tiye, “His abilities are so extraordinary that he is beginning to intimidate his master.”

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

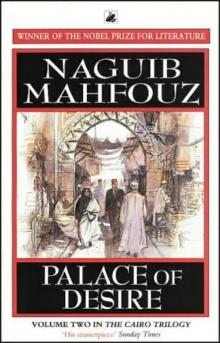

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma