- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

Sugar Street tct-3 Page 2

Sugar Street tct-3 Read online

Page 2

Kamal always felt uncomfortable and uneasy when forced to disagree openly with one of his father's ideas. He replied gently, "We've finished discussing that."

"Every day friends ask if you won't give their children private lessons. You shouldn't reject honest work. Private lessons are a source of substantial income for teachers. The men asking for you are some of the most distinguished inhabitants of this district."

Kamal said nothing, but his face showed his polite refusal. His father asked regretfully, "You refuse and waste your time with endless reading and writing for free. Is that appropriate for an intelligent person like yourself?"

At this point Amina told Kamal, "You ought to love wealth as much as you love learning". Then, smiling proudly, she reminded al-Sayyid Ahmad, "He's like his grandfather. Nothing equaled his love of learning."

Her husband grumbled, "The grandfather again! I mean, washe an important theologian like Muhammad Abduh?"

Although she knew nothing about this distinguished modern reformer, she replied enthusiastically, "Why not, sir? All our neighbors came to him with their spiritual and worldly concerns."

Al-Sayyid Ahmad's sense of humor got the better of him. He laughed and said, "There are more religious scholars like him than you can shake a stick at."

The woman's protest was conveyed by her face, not her tongue. Kamal smiled affectionately but uneasily. He asked their permission to depart and left the room. In the sitting room Na'ima stopped him, wishing to show him her new dress. While she went to get it, he sat down beside Aisha to wait. Like the rest of the family, he indulged Na'ima in order to humor Aisha. But he was also as fond of this beautiful girl as he had been of her mother in the old days. Na'ima appeared with the dress, which he spread out in his hands. He examined it appreciatively and gazed at its owner with love and affection. He was struck by her gentle but extraordinary beauty, which purity and delicacy made magnificently luminous.

Kamal left the room with a heavy heart. It was sad to watch a family age. It was hard to see his father, who had been so forceful and mighty, grow weak. His mother was wasting away and disappearing into old age. He was having to witness Aisha's disintegration and downfall. The atmosphere of the house was charged with warning signs of misery and death.

He ascended the stairs to the top floor, which he called his apartment. He lived there alone, going back and forth between his bedroom and his study, both of which overlooked Palace Walk. He removed his clothes and put on his house shirt. Wrapping his robe around him, he went to the study, where a large desk with bookcases on either side stood near the latticed balcony. He wanted to read at least one chapter of Bergson's The Two Sources of Morality and Religion and to revise for the final time his monthly column in the magazine al-Fikr. This one happened to be about Pragmatism. The happiest part of his day was the period he devoted to philosophy. Lasting until midnight, it was the time as he put it when he felt like a human being. The rest of his day spent as a teacher in al-Silahdar School or in satisfying various needs of daily life was the stamping ground of the animal concealed inside him. That creature's goals were limited to self-preservation and the gratification of desires.

He neither loved nor respected his career but did not openly acknowledge his annoyance with it, especially not at home, for he wished to deprive people of the opportunity of rejoicing at his misfortune. All the same he was an excellent teacher who had won everyone's respect, and the headmaster had entrusted some administrative chores to him. Kamal jokingly accused himself of being a slave, for a slave might have to master work he did not like. The truth was that his desire to excel, which had stayed with him from his youth, compelled him to work hard for recognition. From the beginning he had resolved to win the respect of his pupils and colleagues, and he had achieved that goal. Indeed he was both respected and loved, in spite of his large head and prominent nose. Without any doubt, they or his painful self-consciousness about them were primarily responsible for his powerful determination to fashion a dignified persona. Realizing that these features would cause trouble, he had steeled himself to defend them against the plots of troublemakers. He did not escape the occasional gibe or taunt in class or on the playground but countered these attacks with an unflinching resolve softened by his innate sympathy for others.

His ability to explain the lessons in a way students could understand and his selection of interesting and engaging topics related to the nationalist movement or to memories of the revolution also swayed public opinion among the pupils in his favor. These factors as well as his firmness when it was necessary nipped rebellion in the bud. At first he had been hurt by the taunts, which were extremely effective at stirring up forgotten sorrows, but he was pleased by the high status accorded him by the youngsters, who regarded him with respect, love, and admiration.

His monthly column in al-Fikr magazine had caused him another problem, for he had to worry about the reaction of the headmaster and the other teachers. They might ask if his presentation of ancient and contemporary philosophical ideas that occasionally seemed critical of accepted beliefs and customs was compatible with a teacher's responsibilities. Fortunately none of these colleagues read al-Fikr. He realized at last that only a thousand copies of each issue were printed, of which half were exported to other Arab countries. That fact encouraged him to keep writing for the magazine, without fear of attacks or of losing his job.

During these brief nocturnal periods the English-language teacher at al-Silahdar School was transformed into a liberated voyager who traversed the limitless expanses of thought. He read, pondered, and jotted down observations that he later incorporated into his monthly columns. His efforts were motivated by a desire to learn, a love for truth, a spirit of intellectual adventure, and a longing for alleviation of both the nightmare engulfing him and the sense of isolation concealed within him. He escaped his loneliness by adopting Spinoza's notion of the unity of existence and consoled himself for his humiliations by participating in Schopenhauer's ascetic victory over desire. He put his sympathy for Aisha's misery into perspective by devouring Leibniz's explanation of evil and quenched hisheart's thirst for love by appealing to Bergson's poetic effusions. Yet this continuous effort did not succeed in disarming the anxiety that tormented him, for truth was a beloved as flirtatious, inaccessible, and coquettish as any human sweetheart. It stirred up doubts and jealousy, awakening a violent desire in people to possess it and to merge with it. Like a human lover, it seemed prone to whims, passions, and disguises. Frequently it appeared cunning, deceitful, harsh, and proud. When he felt too upset to work, he would console himself by saying, "I may be suffering, but still I'm alive…. I'm a living human being. Anyone who deserves to be called a man will have to pay dearly in order to live."

117

Looking over the ledgers, keeping the books, and balancing the previous day's sales were all tasks Ahmad Abd al-Jawad performed as expertly and exactly as ever, but he accomplished them with greater difficulty now that he was old and sick. He looked almost pitiable as he sat hunched over his ledgers, beneath the framed inscription reading "In the Name of God," his gray mustache almost concealed by his large nose, which looked bigger now because of the thinness of his face. The appearance of his assistant, Jamil al-Hamzawi, almost seventy, was even more pathetic, and the moment he finished waiting on a customer, he would collapse, breathless, on his chair.

Ahmad told himself rather resentfully, "If we were civil servants, our pensions would spare us work and effort at our age". Raising his head from the accounts, he announced, "Sales are still off because of the economic crisis."

Al-Hamzawi pursed his pale lips with annoyance and said, "No doubt about it. But this year's better than last year, and that was better than the one before. Praise God in any event."

Merchants called the period commencing with 1930 the days of terror. Isma'il Sidqy had dominated the country's politics, and scarcity had governed its economy. From morning to night there had been news of bankruptcies and liquidations. Throwi

ng up their hands in dismay, businessmen had wondered what the morrow had in store for them. Al-Sayyid Ahmad was definitely one of the lucky ones. Although bankruptcy had threatened him year after year, he had never gone over the brink.

"Yes, praise God in any event."

He noticed that Jamil al-Hamzawi was gazing at him in a strange, hesitant, and embarrassed way. What could be on the man's mind? Al-Hamzawi stood up to move his chair closer to the desk. Then, sitting down again, he smiled uneasily. It was bitterly cold, although the sun was shining brightly. Gusts of wind rattled the doors and windows, making a whistling sound.

Al-Sayyid Ahmad sat up straight and remarked, "Say what you want to. I'm sure it's important."

Lowering his gaze, al-Hamzawi said, "I'm in an awkward position. I don't know how to put it…."

His employer encouraged him: "I've spent more time with you than with my own family…. You should feel free to express yoursel f frankly."

"Our years together are what make it so difficult for me, al-Sayyid, sir."

"Our years together!" he thought. This possibility had never occurred to him.

"You want to … really?"

Al-Hamzawi answered sadly, "The time has come for me to retire. God never asks a soul to bear more than it can."

Al-Sayyid Ahmad felt depressed. Al-Hamzawi's retirement was a harbinger of his own. How could he look after the store by himself? He was old and sick.

He looked anxiously at his assistant, who said emotionally, "I'm really sorry. But I'm no longer up to the work. That time has vanished. Still, I've arranged things so you won't be left alone. My place will be taken by someone better able to assist you than I am."

His trust in al-Hamzawi's honesty had relieved him of half of his labors. How could a man of sixty-three start tending a store again from dawn to dusk? He said, "It's when a man retires and sits at home that his faculties begin to fail. Haven't you noticed that in civil servants with pensions?"

Smili ng, Jamil al-Hamzawi answered, "In my case, decline has preceded retirement."

Al-Sayyid Ahmad laughed suddenly as if to mask his discomfort and them observed, "You old rascal, you're deserting me in response to your son Fuad's requests."

Al-Hamzawi cried out indignantly, "God protect us! The state of my health is evident to everyone. It is the only reason."

Whc could say? Fuad was an attorney in the government judicial service. A person like that would not want his father to continue working as a clerk in a store, not even when the owner had made it possible for him to earn his government post. Yet al-Sayyid Ahmad sensed that his candor had distressed his excellent assistant. So he tried to cover his tracks by asking courteously, "When will Fuad be transferred back to Cairo?"

"This summer, or next summer at the latest…". The moments that followed were heavy with embarrassment until al-Hamzawi, matching his employer's gracious tone, added, "Once he's settled in Cairo with me, I'll have to think about finding a bride for him. Isn't that so, al-Sayyid, sir? He's my only son out of eight children. I've got to arrange a marriage for him. Whenever I think about this, a refined young lady comes to mind your granddaughter". He glanced quickly and inquisitively at his employer's face before stammering, "Of course, we're not of your class…."

Al-Sayyid Ahmad found himself forced to reply, "May God forgive us, Uncle Jamil. We've been brothers for ages."

Had Fuad encouraged his father to sound out the situation? To have a position as a government attorney was outstanding, and the most important thing about a person's family was that they be good people. But was this the time to discuss marriage?

"Tell me first of all whether you're determined to retire."

A voice called out from the door of the shop, "A thousand good mornings!"

Although annoyed at having this important conversation interrupted, al-Sayyid Ahmad smiled to be polite and answered, "Welcome! Welcome!" Then he gestured toward the chair al-Hamzawi had vacated, saying, "Please have a seat."

Zubayda sat down. Her body seemed bloated, and her face was veiled by cosmetics. There was no trace of the gold jewelry that had once decorated her neck, wrists, and ears, and nothing remained of her former beauty.

As usual, al-Sayyid Ahmad tried to make her feel at home, but he treated her like any other visitor. His heart was displeased by this call, for whenever she came she burdened him with requests. He asked about her health, and she replied that she was not suffering from anything, "Praise God."

After a moment of silence, he said again, "Welcome, welcome. …"

She smiled gratefully but seemed to sense the lack of enthusiasm lurking behind his polite remarks. Pretending to be oblivious to the enveloping atmosphere of disinterest, she laughed. Time had taught her how to control herself. She observed, "I don't like to take up your time when you're busy, but you're the finest man I've ever known. Either give me another loan or find someone to buy my house. I wish you'd buy it yourself!"

Ahmad Abd al-Jawad sighed and said, "Me? If only I could…. Times have changed, Sultana. I keep telling you frankly how things are, but you don't seem to believe me, Sultana."

She laughed to hide her disappointment and then said, "The sultana's ruined. What can she do?"

"Last time I gave you what I could, but my circumstances won't allow me to repeat that."

She asked anxiously, "Couldn't you find someone to buy my house?"

'Til look for a buyer. I promise you that."

She answered thankfully, "This is what I expected from you, for you're the most generous of men". Then she added sadly, "The world's not the only thing that's changed. People have changed even more. May God pardon them. In my glory days, they vied to kiss my slippers, but now if they spot me on the street they cross over to the other side."

It was inevitable for a person to be disappointed by something in life, in fact by many thingshealth, youth, or other people — but where were those days of glory, melodies, and love?

"You're partly to blame, Sultana. You never made any provision for this time of your life."

She sighed sorrowfully and said, "Yes. I'm not like your 'sister' Jalila. She doesn't mind whose reputation is tarnished, as long as she gets rich. She's accumulated a lot of money and several houses. Besides, God has surrounded me by thieves. Hasan Anbar was depraved enough to charge me a whole pound for a pinch of cocaine when it was scarce."

"Curses…."

"On Hasan Anbar? A thousand!"

"No, on cocaine."

"By God, cocaine's a lot more merciful than people."

"No. No, it's really sad that you've succumbed to its evil influence."

With despondent resignation she admitted, "It has sapped my strength and destroyed my wealth. But what can I do? When will you find me a buyer?"

"At the first opportunity, God willing."

She rose, saying reproachfully, "Listen, the next time I visit you, smile as though you really mean it. I can bear insults from anyone but you. I know my requests are a nuisance, but I'm in straits known only to God. In my opinion, you're the noblest man alive."

He told her apologetically, "Don't start imagining things. It's just that I was preoccupied with an important question when you arrived. As you know, a merchant's worries never end."

"May God relieve you of them all."

Escorting her to the door, he bowed his head to show his appreciation for her comment. Then he bade her farewell: "You're really most welcome, any time". He noticed the eloquent look of distress and defeat in her eyes and felt sorry for her. Returning to his seat with a heavy heart, he looked at Jamil al-Hamzawi and remarked, "What a world!"

"May God spare you its evils and treat you to its blessings". But al-Hamzawi's tone grew harsh when he continued: "Still, it's the just reward for a debauched woman."

Ahmad Abd al-Jawad shook his head quickly and briefly as if to protest silently against the cruelty of this moralizing remark. Then resuming the merrier tone of voice he had used before Zubayda's interruption, he asked, "Are you s

till resolved to desert us?"

The other man answered uneasily, "It's not desertion but retirement. And I'm very sorry about it."

"Words… like the ones I used to deceive Zubayda a minute ago."

"God forbid! I'm speaking from my heart. Don't you see, sir, that old age has almost carried me off?"

A customer came into the store, and al-Hamzawi went to wait on him. Then the voice of an elderly man cried out flirtatiously from the doorway, "Who's that person as handsome as the full moon sitting behind the desk?"

Shaykh Mutawalli Abd al-Samad stood there in a crude, tattered, colorless gown and torn red leather shoes, his head wrapped in a camel's-hair muffler. Propping himself up with a staff, he gazed with bloodshot eyes at the wall next to the desk, thinking that he was looking at the proprietor.

In spite of his worries, al-Sayyid Ahmad smiled and said, "Come here, Shaykh Mutawalli. How are you?"

Opening a toothless mouth, the old man yelled, "High blood pressure, go away! Health, return to this lord of men."

Al-Sayyid Ahmad stood up and walked toward him. The shaykh stared in his direction but backed away as if preparing to flee. Then turning around in a circle, he pointed in each of the four directions and shouted, "You'll find relief here… and here … and here … and here". Exiting to the street, he intoned, "Not today. Tomorrow. Or the next day. Say: God knows best". He strode off with long steps that seemed incongruous for a man who looked so feeble.

118

The extended family returned to its roots every Friday, and the old house came alive with children and grandchildren. This happy tradition had never lapsed. Since Umm Hanafi now held pride of place in the kitchen, Amina was no longer the heroine of the day. Still, the mistress never tired of reminding her family that the servant was her pupil. Amina's desire for praise became more pronounced as she sensed increasingly that she did not deserve it. Although a guest, Khadija alwayshelped with the cooking too.

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

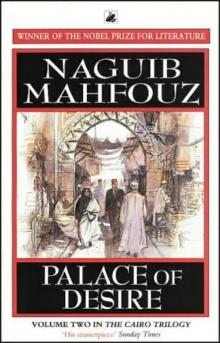

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma