- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

Karnak Café Page 2

Karnak Café Read online

Page 2

“So now we’re back to our original point,” I said with some emphasis.

“You realize that I’m in love, don’t you?” she asked me forthrightly.

True enough, I had noticed certain things, but now she had caught me red-handed.

“You’re no fool,” she said, “so don’t even ask me who it is.”

“Hilmi Hamada?” I inquired with a smile.

Without even excusing herself she made her way back to her chair; once there she threw me the sweetest of smiles. At one time I had thought it was Isma‘il al-Shaykh, but then I discovered that he and Zaynab Diyab were very close. After that things had become clearer. Hilmi Hamada was a very trim and handsome young man, always very excitable when there was an argument. Qurunfula was quite frank with me. She had been the one to make the amorous overtures, in fact right in front of his young friends. On one occasion she was sitting next to him and listening to him speak his mind about some political controversy: “Long live everything you want to live,” she yelled, “and death to anyone you want to see dead!”

She invited him up to her apartment on the fourth floor of the building (the café was on the first floor). Once there she gave him a sumptuous welcome. The sitting room was decked with flowers, there was a huge spread on the table, and dance music was playing on the tape recorder.

“He loves me too,” she told me confidently, “you can be quite sure of that.” She paused for a short while, then continued in a more serious tone, “But actually he has no idea how much I love him.” Then there was a flash of anger. “One of these days I expect he’ll just get up and leave for good … but then, what else is new?” That last phrase came out with a shrug of the shoulders.

“You’re aware of everything, and yet you still insist on going your own way.”

“That’s a pretty fatuous remark, but it might just as well serve as a motto for life itself.”

“On behalf of the living,” I commented with a smile, “allow me to thank you.”

“But Hilmi’s serious and generous too. He was the first person to get enthusiastic about my project.”

“And which project might that be, if you please?”

“Writing my memoirs. I’m absolutely crazy about the idea. The only thing holding me back is that I’m no good at writing.”

“Is he helping you write them down on a regular basis?”

“Yes, he is. And he’s very keen about it too.”

“So he’s interested in art and history?”

“That’s one side of it. Other parts deal with the secret lives of Egypt’s men and women.”

“People from the previous generation?”

“The present one as well.”

“You mean, scandals and things like that?”

“Once in a while there’s a reference to some scandals, but I have more worthwhile goals than just that.”

“It sounds risky,” I said, introducing a note of caution.

“There’ll be an uproar when it’s published,” she went on with a mixture of pride and concern.

“You mean, if it is ever published,” I commented with a laugh.

She gave me a frown. “The first part can be published with no problems.”

“Fine. Then I’d leave the second part to be published in the fullness of time.”

“My mother lived till she was ninety,” she responded hopefully.

“And may God grant you a long life too, Qurunfula,” I said, in the same hopeful tone.

There came a day when I arrived at the café only to find all the chairs normally occupied by the young people empty. The entire place looked very odd, and a heavy silence hung over everything. The old men were busy playing backgammon and chatting, but Qurunfula kept casting anxious glances toward the door. She came over and sat down beside me.

“None of them have come,” she said. “What can have happened?”

“Maybe they had an appointment somewhere else.”

“All of them? He might have let me know, even if it was just a phone call.”

“I don’t think there’s anything to worry about.”

“Perhaps not,” she said sharply, “but there’s plenty to be angry about.”

Evening turned into night, but none of them showed up. The following evening it was the same story. Qurunfula’s mood changed, and she became a bundle of nerves, going in and out of the café.

“How do you explain it all?” she asked.

I shook my head in despair.

“Oh, they’re just youngsters,” was Zayn al-‘Abidin’s contribution to the conversation. “They never stay anywhere for too long. They’ve gone somewhere else that suits them better.”

Qurunfula lost her temper and rounded on him. “What a stupid idiot you are!” she said. “Why don’t you go somewhere that suits you better as well?”

“Oh no,” he replied with an imbecilic laugh, “I’m already in the most suitable place.”

At this point I did my best to smooth things over. “I’m sure we’ll see them again at any moment.”

“The worry of it all is killing me,” she whispered in my ear.

“Don’t you know where he lives?” I asked delicately.

“No, I don’t,” she replied. “It’s somewhere in the Husayniya Quarter. He’s a medical student, but the college is closed for summer vacation. As you can tell, I’ve no idea where he lives.”

Days and weeks passed, and Qurunfula almost went out of her mind. I joined her in her sorrow.

“You’re destroying yourself,” I told her. “Have a little pity, at least on yourself.”

“It’s not pity I need,” she replied. “It’s him.”

Zayn al-‘Abidin avoided any further tirades by saying nothing and keeping his thoughts to himself. Actually, he was feeling profoundly happy about the new situation, but he managed to keep his true feelings hidden by looking glum and puffing away on his shisha.

One day Taha al-Gharib spoke up. “I hear there have been widespread arrests.”

No one said a word. After this moment of loaded silence I thought I would try to be as helpful as possible. “But these young folk all support the revolution,” I said.

That led Rashad Magdi to insert his opinion. “And there’s a not inconsiderable minority of them who oppose it.”

“It’s quite clear what’s happened,” Muhammad Bahgat suggested. “They decided to put the guilty ones in prison, so they’ve dragged all the friends in too. That way the investigation will be complete.”

Qurunfula kept following this conversation. The expression on her face was one of utter confusion, and it made her look almost stupid. She adamantly refused either to understand or be convinced by anything she was hearing. Meanwhile the conversation continued with everyone contributing their own ideas about what was happening.

“Imprisonment is really scary.”

“The things you hear about what’s being done to prisoners are even more scary.”

“Rumors like those are enough to make your stomach churn.”

“There’s no judicial hearing and no defense.”

“There’s no legal code in the first place!”

“But people keep saying that we’re living through a revolutionary process that requires the use of extraordinary measures like these.”

“Yes, and they go on to say that we all have to sacrifice freedom and the rule of law, but only for a short while.”

“But this revolution is thirteen years old and more. Surely it’s about time things settled down and became more stable.”

Qurunfula started neglecting her job. She would spend all or part of the day somewhere else; sometimes she didn’t appear for twenty-four hours at a stretch. It would be left to ‘Arif Sulayman and Imam al-Fawwal to run the café.

When she reappeared, she used to tell us that she had been to see all the influential people she knew from both past and present. She had asked them all for information, but nobody knew anything. “What you keep getting,” she told us,

“are totally unexpected remarks, like ‘How are we supposed to know,’ or ‘I’d be careful about asking too many questions,’ or even worse, ‘If I were you, I wouldn’t offer any young folk hospitality in your café!’ What on earth has happened to the world?”

With that my own thoughts went off on an entirely new tack, the primary impulse being a feeling of profound sadness. Yes indeed, I told myself, this life we’re living does have its painful and negative aspects, and yet they are simply necessary garbage to be thrown away in contempt by the entire gigantic social structure. However, they should not blind us to the majesty of the basic concept and its scope. During the period when Saladin was winning his glorious victory over the Crusaders, how do we know what the average street-dweller in Cairo was living through? While Muhammad ‘Ali was busy creating an Egyptian empire in the nineteenth century, how much did the Egyptian peasants have to suffer? Have we ever tried to imagine what it must have been like during the time of the Prophet himself, when the new faith caused deep rifts between father and son, brother and brother, and husband and wife? Friendships were torn apart, and long-standing traditions were replaced by new hardships. And if we keep all these precedents in mind, should we not be willing to endure a bit of pain and inconvenience in the process of turning our state, the most powerful in the Middle East, into a model of a scientific, socialist, and industrial nation? While all these notions were buzzing inside my head, I had the sense that, by applying such logic, I could even manage to convince myself that death itself had its own particular requirements and benefits.

And then, all of a sudden one afternoon, the familiar, long-lost faces reappeared in the doorway: Zaynab Diyab, Isma‘il al-Shaykh, Hilmi Hamada, and some others as well. We never saw the rest of them again. Their arrival prompted an instantaneous outburst of pure joy, and we all welcomed them back with open arms. Even Zayn al-‘Abidin joined in the festivities. Qurunfula sank back into her chair, as though she were taking a nap or had just fainted. She neither spoke nor moved. Hilmi Hamada went over to her.

“I’ll get my revenge on you!” she sobbed and then burst into tears.

“Where on earth have you all been?” someone asked.

“On a trip,” more than one voice answered.

They all roared with laughter, and everyone seemed happy again. And yet their faces had altered. The shaved heads made them look peculiar, and the old youthful sparkle in their eyes had gone, replaced by listless expressions.

“But how did it all happen?” someone (maybe Zayn al-‘Abidin) asked.

“No, no!” yelled Isma‘il al-Shaykh, “please spare us that.…”

“Oh, come on,” yelled Zaynab Diyab gleefully. “Forget about all that. We’ve come through it, and we’re all safe and sound.”

There was one name that I kept hearing, although I have no idea how it came up or who was the first person to mention it: Khalid Safwan, Khalid Safwan. So who was this Khalid Safwan? A detective? Prison warden? Several of them kept mentioning his name. I caught brief glimpses of the expressions on their faces; under the exterior veil the suffering and sense of disillusionment were almost palpable.

True enough, life at Karnak Café resumed its daily routine, and yet a good deal of the basic spirit of the place had been lost. A thick partition had now been lowered, one that turned the time they had been away into an ongoing mystery, an engrossing secret that left questions of all kinds unanswered. Beyond that, and in spite of all the lively chatter and jollity, a new atmosphere of caution pervaded the place, rather like a peculiar smell whose source you cannot trace. Every joke told had more than one meaning to it; every gesture implied more than one thing; in every innocent glance there was also a feeling of apprehension.

One day Qurunfula opened up to me. “Those young folk have been through a great deal,” she said.

“Has he told you anything about it?” I asked eagerly.

“No,” she replied, “he doesn’t say a single word. But that in itself is enough.”

Yes indeed, that in itself was enough. After all, we were all living in an era of unseen powers—spies hovering in the very air we breathed, shadows in broad daylight. I started using my imagination to reflect upon the past. Roman gladiators, courts of inquiry, reckless reprobates, criminal behavior, epics of suffering, ferocious outbursts of violence, forest clashes. I had to rescue myself from these reflections on human history, so I reminded myself that for millions of years dinosaurs had roamed the earth, but it had only taken a single hour to eradicate them all in a life-and-death struggle. All that remained now were just one or two huge skeletons. It seems that, whenever darkness envelops us, we are intoxicated by power and tempted to emulate the gods; with that, a savage and barbaric heritage is aroused deep within us and revives the spirit of ages long since past.

At this particular moment all the information I had was filtered through the imagination. It was only years later and in very different circumstances that people finally began to open their hearts, hearts that had previously been locked tight shut. They provided me with gruesome details, all of which helped explain certain events that at the time had seemed completely inexplicable.

Zayn al-‘Abidin never for a moment gave up hope, making a virtue out of patience. He kept on watching and waiting for just the right moment. Needless to say, Hilmi Hamada’s return had completely ruined his plans. It may have been his fear of seeing his quest for Qurunfula end in failure that stirred an emotion buried deep inside him. In any case, it led him to cross a line and abandon his normally cautious demeanor. One day he put his suppressed feelings into words right in front of Qurunfula.

“It seems to me,” he stated recklessly, “that the presence of these young people in the café may be having a very negative effect on the place’s reputation.”

Qurunfula shot right back at him. “So when are you planning to leave?” she asked.

He chose to ignore her remark and instead continued in a suitably homiletic tone, “I do have a worthwhile project in mind, one with a number of benefits to it.” He now turned toward me, looking for support. “What do you think of the project?” he asked.

For my part I addressed a question to Qurunfula. “Wouldn’t you like to have a larger share in the national capital?”

“But it’s not just the capital he’s after,” she replied sarcastically. “He wants the woman who owns it as well!”

“Not so,” insisted Zayn al-‘Abidin. “My proposal only involves the business itself. Matters of the heart rest in the hands of God Almighty.”

She stopped arguing with him. It seemed as though she was totally consumed by her infatuation. Every time I watched her playing the role of the blind lover, I felt a tender sympathy for her plight. I had no doubt in my mind that that boy loved her in an adolescent kind of way; for her part she certainly knew how to attract him and keep him happy, while he was able to enjoy her affection to the full. But how long would it last? On that particular score she used to share some of her misgivings with me, but at the same time she felt able to tell me with complete confidence that he certainly wasn’t a gigolo.

“He’s as decent as he is intelligent. He’s not the sort to sell himself.”

I had no reason to doubt her word. The boy’s appearance and the way he talked both tended to confirm her opinion, although once in a while his expression would turn cryptic and even violent. But speculation of this kind was essentially pointless when one was faced with the incontrovertible fact that Qurunfula was well into the autumn of her years; at this stage in her life, money and fidelity were the only things she could now offer from among the many forms of enticement she had previously had at her disposal.

One time Zayn al-‘Abidin had a word in my ear. “Don’t be fooled by his appearance,” he said.

I immediately realized he was talking about Hilmi Hamada. “What do you know about him?” I asked.

“Look, he’s either a world-class schmoozer or a complete and utter phony!” For a few moments he said nothing, then wen

t on, “I’m pretty sure he’s in love with Zaynab Diyab. Any day now he’s going to grab her away from Isma‘il al-Shaykh.”

I was troubled by his comments; not because I thought he was lying, but rather because they tended to confirm what I had recently been noticing myself, the way Hilmi and Zaynab kept on chatting to each other in a certain way. I had frequently asked myself whether it was just a case of close friendship or something more than that.

My friendship with Qurunfula was now on a firm enough footing for me to summon up the necessary courage to ask her a crucial question. “You’ve had a lot of experience in matters of life and love, haven’t you?

“No one can have any doubts on that score,” she responded proudly.

“And yet …,” I whispered.

“And yet what?”

“Do you think your love affair is going to have a happy ending?”

“When you’re really and truly in love,” she insisted, “it’s that very feeling that allows you to forget all about such things as wisdom, foresight, and honor.”

And that forced me to conclude that there is never any point in discussing love affairs with their participants.

And then the young folk disappeared again. As with the first time, it all happened suddenly and with no warning whatsoever.

This time, however, none of us needed to go through tortures of doubt or ask probing questions. Nevertheless we were all scared and disillusioned.

Qurunfula staggered under the weight of this new blow. “I never in my life imagined,” she said, “that I’d have to go through it all again.” That said, the sheer agony of the whole thing drove her upstairs to her apartment.

Once she had left, it was easier for the rest of us to talk.

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

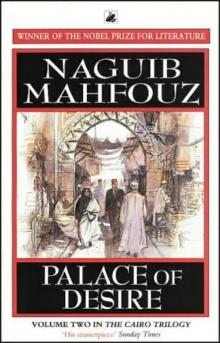

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma