- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

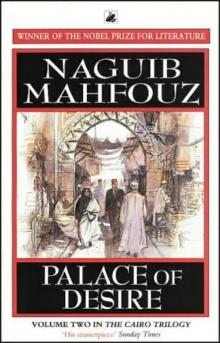

Palace of Desire tct-2 Page 3

Palace of Desire tct-2 Read online

Page 3

"Of what importance is the date? The calendar has a magic that makes us imagine a memory can be resurrected and revived, but nothing returns. You'll keep on searching for the date, repeating: the beginning of the second year at school, October or November, during Sa'd Zaghlul's journey to Upper Egypt, and before he was exiled for the second time. No matter how much you consult your memory, the evidence, and events of the day, you'll simply end up clinging desperately to your attempt to rediscover that lost happiness and a time that has disappeared forever. If only you had held out your hand when you were introduced, as you almost did, she would have shaken it and you would have experienced her touch. Now you imagine it repeatedly with feelings of both skepticism and ecstasy, for she seems to be a creature with no physical body. Thus a dreamlike opportunity was lost, which — along with that moment — will never return. Then she directed her attention to your two friends, conversing freely with them while you crouched in your seat in the gazebo, racked by the anxiety of a person fully imbued with the traditions of the Husayn district. At last you asked yourself whether there might not be special rules of etiquette for mansions. Perhaps it was a breath of perfumed air originating in Paris, where the beloved creature had grown up. Then you submerged yourself in the melody of her voice, savoring its tones, becoming intoxicated by its music, and soaking up every syllable that slipped out. Perhaps you did not understand, you poor dear, that you were being born again at that very moment and that like a newborn baby you had to greet your new world with alarm and tears.

"The girl's melodious voice remarked, "We're going this evening to see The Coquette." With a smile, Isma'il asked her, 'Do you like the star, Munira al-Mahdiya?' She hesitated a moment as was fitting for a half-Parisian girl. Then she replied, 'Mama likesher.' Husayn, Isma'il, and Hasan all got involved in a conversation about the outstanding musicians of the day: Munira al-Mahdiya, Sayyid Darwish, Salih Abd al-Hayy, and Abd al-Latif al-Banna.

"Suddenly I was taken by surprise to hear the melodious voice ask, 'What about you, Kamal? Don't you like Munira?'

"Do you recall this revelation that descended on you so unexpectedly? I mean do you recall the natural harmony of it? It was not a phrase but a magical tune that came to rest deep inside you where k sings on silently to an attentive heart, which experiences a heavenly happiness unknown to anyone but you. How astounded you we re when greeted by it. It was like a voice from the heavens singling you out to address you by name. In a single draft you imbibed unparalleled glory, bliss, and grace. Immediately afterwards you would have liked to echo the Prophet's words when he would feel a revelation coming and cry out for help: 'Wrap me up! Cover me with my cloak!'

"The n you answered her, although I don't remember how. She stayed a few minutes longer before saying goodbye and departing. The charming look of her black eyes added to her fascinating beauty by revealing an agreeable candor — a daring that arose from self-confidence, not from licentiousness or wantonness — as well as an alarming arrogance, which seemed to attract and repel you at the same time.

"Her beauty has a fatal attraction. I don't understand its essence and I know nothing comparable. I often wonder if it's not the shadow of a much greater magic concealed within her. Which of these two forms of enchantment makes me love her? They're both puzzles. The third puzzle is my love. Although that moment fades farther into the past every day, its memories are eternally planted in my heart because of its associations with place, time, names, company, and remarks. My intoxicated heart circles through them until it imagines they are life itself, wondering somewhat skeptically whether any life exists beyond them. Had there really been a time when my heart was empty of love and my soul devoid of that divine image? At times you were so ecstatically happy that you grieved over the barrenness of your past. At other times you were so stung by pain that you pined for the peace that had fled. Caught between these two emotions, your heart could find no repose. It proceeded to search for relief from various spiritual opiates, finding them at different times in nature, science, and art, but most frequently in worship. From the innermost reaches of your awakened heart there flared up a passionate desire for divine delights…. 'People, you must love or die.' That was what your situation seemed to imply as you proudly and grandly strode along bearing the light of love and its secrets inside you, boasting of your elevation over life and other living creatures. A bridge strewn with the roses of happiness linked you to the heavens. Yet at times, when alone, you fell victim to a painful, sick, conscious reckoning of your shortcomings and to merciless brooding about them. These confined you to your little self, your modest world, and the mortal level of well-being.

"Oh Lord, how can a person re-create himself afresh? This love is a tyrant. It flies in the face of other values, but in its wake your beloved glistens. Normal virtues do not improve it and ordinary defects of character do not diminish it. Such contrasts appear beautiful in its crown of pearls and fill you with awe. In your opinion, was it in any way demeaning for her to have disregarded the customs most people observe? Of course not… in fact it would have been more demeaning if she had observed them. Occasionally you like to ask yourself: What is it you want from her love? I answer simply that I want to love her. When life is gushing through a soul, is it right to question what the point is? There's no ulterior motive for it. It's only tradition that has linked the two words: love' and 'marriage.' It is not merely the differences of age and class that make marriage an impossible goal for someone in my situation. It is marriage itself, for it seeks to bring love down from itsheaven to the earth of contractual relationships and sweaty exertion.

"Someone insists on making you account for your actions and asks what you have gained from falling in love with her. Without any hesitation I reply, fascinating smile, the invaluable gift of hearing her say my name, her visits to the garden on rare blissful occasions, catching a glimpse of her on a dewy morning when the school bus is carrying her off, and the way she teases my imagination in ecstatic daydreams or drowsy interludes of sleep.' Then your madly yearning soul asks, 'Is it absolutely out of the question that the beloved might take some interest in her lover?' Don't give in to false hopes. Tell your soul, 'It is more than enough if the beloved will remember your name when we meet again.'"

"Quick. To the bathroom. Aren't you late?"

Registering his surprise, Kamal's eyes looked at Yasin, who had returned to the room and was drying his head with a towel. Kamal jumped out of bed. His body looked long and thin. He cast a glance in the mirror as though to examine his huge head, protruding forehead, and a nose that appeared to have been hewn from granite, it was so large and commanding. He took his towel from the bed frame and headed for the bathroom.

AJ-Sayyid Ahmad had finished praying. Now he lifted his powerful voice in his customary supplications for his children and himself, asking God for guidance and protection in this world and the next. At the same time Amina was setting out the brea kfast. Then she went to invite him in her meek voice to have breakfast. Going to the room shared by Yasin and Kamal, she repeated her invitation.

The three men took their places around the breakfast tray. The father ir voked the name of God before taking some bread to mark the beginning of the meal. Yasin and then Kamal followed his lead. Meanwhile the mother stood in her traditional spot next to the tray with the water jugs. Although the two brothers appeared polite and submissive, their hearts were almost free of the fear that had afflicted them in former times in their father's presence. For Yasin it was a question of his twenty-eight years, which had bestowed on him some of the distinctions of manhood and served to protect him from abusive insults and miserable attacks. Kamal's seventeen years and success in school also afforded him some security, if not as much as Yasin. At least his minor lapses would be excused and tolerated. During the last few years he had become accustomed to a less brutal and terrifying style of treatment from his father. Now it was not uncommon for a brief conversation to take place between them. An intimidating silence had previously

dominated their time together, except when the father had asked one of them a question and the son would hastily answer as best he could, even if his mouth was full of food.

Yes, it was no longer out of the ordinary for Yasin to address his father. He might say, for example, "I visited Ridwan at his grandfather's house yesterday. He sends you his greetings and kisses your hand."

Al-Sayyid Ahmad would not consider such a statement to be impudent or out of line and would answer simply, "May our Lord preserve him and watch over him."

It was not out of the question at such a moment for Kamal to ask his father politely, "When will custody of Ridwan revert to his father, Papa?" In that way he demonstrated the dramatic transformation of his relationship to his father.

Al-Sayyid Ahmad had replied, "When he turns seven," instead of screaming, "Shut up, you son of a bitch."

One day Kamal had attempted to establish the last time his father had insulted him. He had finally recalled that it had been about two years before, or a year after he had fallen in love, for he had begun to date events from that moment. At the time, he had felt that his friendship with young men like Husayn Shaddad, Hasan Salim, and Isma'il Latif demanded a large increase in his pocket money, so that he could keep up with them in their innocent amusements. He had complained to his mother, asking her to request the desired increase from his father. Although it was not easy for the mother to raise such an issue with the father, it was less difficult than it had once been, because of the change that had occurred in his treatment of her after Fahmy's death. Commending the new ties of friendship to important families with which h er son had been honored, she had mentioned the request to her husband. Al-Sayyid Ahmad had then summoned Kamal and poured out his anger on the boy, yelling, "Do you think I'm at the beck and call of you and your friends? Cursed be your father and their fathers too."

Thinking the matter at an end, Kamal had left disappointed. To his surprise, the following day at the breakfast table the man had asked about his friends. On hearing the name Husayn Abd al-Hamid Shaddad, he had inquired with interest, "Is your friend from al-Abbasiya?"

Kamal had answered in the affirmative, his heart pounding.

Al-Sayyid Ahmad had said, "I used to know his grandfather Shaddad Bey. I know that his father Abd al-Hamid Bey was exiled, because of his ties to the Khedive Abbas…. Isn't that so?"

Kamal had replied in the affirmative once more, while contending with the strong emotion aroused by this reference to the father of his beloved. He had remembered immediately what he knew of the years her family had spent in Paris. His beloved had grown up in the brilliance of the City of Light. He had been seized by a feeling of renewed respect and admiration for his father along with redoubled affection. He had considered his father's acquaintance with the grandfather of his beloved to be a magical charm linking him, however distantly, to the home from which his inspiration flowed and to the source of everything splendid. Shortly thereafter his mother had brought him the good news that his father had agreed to double his allowance. Since that day Karnal had not been cursed by his father again, either because he had done nothing to merit it or because his father had decided to spare him further insults.

Kamal stood beside his mother on the balcony, which was enclosed with latticework. They were watching al-Sayyid Ahmad walk along the street and respond with dignity and grace to the greetings of Uncle Hasanayn the barber, al-Hajj Darwish, who so'd beans, al-Fuli the milkman, Bayumi the drinks vendor, and Abu Sari' who sold seeds and other snacks.

When Kamal returned to his room, he found Yasin standing in front of the mirror, grooming himself patiently and carefully. The boy sat on a sofa between the two beds and studied his older brother's body, which was tall and full, and his plump, ruddy face with its enigmatic smile. He harbored sincere fraternal affection for Yasin, although when he scrutinized his brother visually or mentally he was never able to overcome the sense of being in the presence of a handsome domestic animal. Although Yasin had been the first person to make his ears resound with the harmonies of poetry and the effusions of stories, Kamal, who now thought that love was the essence of life and the spirit, would wonder whether it was possible to imagine Yasin in love. The response would be a laugh, whether voiced or internal. Yes, what relationship could there be between love and this full belly? What could this beefy body know of love? What love was there in this sensual, mocking look? He could not help feeling disdain, softened by love and affection. There were times, though, when he admired or even envied Yasin, especially when his love was troubled by a spasm of pain.

Yasin, who had once personified culture for him, now seemed almost totally lacking in it. In the old days Kamal had considered him a scholar with magical powers over the arts of poetry and storytelling. What little knowledge Yasin had was based on superficial reading confined to the coffee hour, or a portion of it, as he went back and forth, without subjecting himself to effort and strain, between al-Hamasa, which was a medieval anthology of poetry, and some story or other, before he rushed off to Ahmad Abduh's coffeehouse. His life lacked the radiance of love and any yearnings for genuine knowledge. Yet Kamal's fraternal affection for his brother was in no way diminished by such realizations.

Fahmy had not been like that. He was Kamal's ideal, both romantically and intellectually, but eventually Kamal's aspirations had reached beyond Fahmy's. He was afflicted by a compelling doubt that a girl like Maryam could inspire genuine love of the sort illuminating his own soul. He was also skeptical that the legal training his late brother had chosen was really equivalent to the humanitieshe was so eager to study.

Kamal uninhibitedly considered those around him with an attentive and critical eye but stopped short when it came to his father. The man appeared to him to be above any criticism, a formidable figure mounted on a throne.

"You're like a bridegroom today. We're going to celebrate your academic achievements. Isn't that so? If you weren't so skinny, I could find nothing to criticize."

Smiling, Kamal replied, "I'm content to be thin."

Yasin cast a last glance at himself in the mirror. Then he placed the fez on his head and carefully tilted it to the right, so it almost touched his eyebrow. He belched and commented, "You're a big donkey with a baccalaureate. Relax and take time to enjoy your food. This is your vacation. How can you feel tempted to read twice as much during your school holiday as you do during the academic year? My God, I'm not guilty of slenderness or of association with it". As He left the room with his ivory fly whisk in his hand, he added, "Don't forget to pick out a good story for me. Something easy like 'Pardaillan' or 'Fausta' by Michel Zevaco. Okay? In the old days you'd beg me for a chapter from a novel. Now I'm asking you to provide me with stories."

Kamal rejoiced at being left to his own devices. He rose, muttering to himself, "How can I put on weight when my heart never slumbers?"

He did not like to pray except when he was alone. Prayer for him was a sacred struggle in which heart, intellect, and spirit all participated. It was the battle of a person who would spare no effort to achieve a clear conscience, even if he had to chastise himself time and again for a minor slip or a thought. His supplications after the prescribed prayer ritual were devoted entirely to his beloved.

74

Abd al-Muni'm: "The courtyard's bigger than the roof. We've got to take the cover off the well to see what's in it."

Na'iina: "You'll make Mama, Auntie, and Grandma angry."

Uthman: "No one will see us."

Ahmad: "The well's disgusting. Anyone who looks in it will die."

Abd al-Mun'im: "We'll get the cover off, but look at it from a distance". Then he continued in a loud voice, "Come on. Let's go."

Blocking the door to the stairway, Umm Hanafi protested, "I don't have any strength left to keep going up and down. You said, 'Let's go up on the roof,' so we did. You said, 'Let's go down to the courtyard,' and we did. 'Let's go up to the roof So we came up another time. What do you want with the courtyard? … The air's hot

down there. Up here we have a breeze, and soon the sun will set."

Na'ima: "They're going to take the cover off the well to look ink."

Umm Hanafi: "I'll call Mrs. Khadija and Mrs. Aisha."

Abd al-Muni'm: "Na'ima's a liar. We won't raise the lid. We won't go anywhere near it. We'll play in the courtyard a little and then come back. You stay here till we return."

Umm Hanafi: "Stay here!.. I have to follow your every step, may God guide you. There's no place in the whole house more beautiful than the roof terrace. Look at this garden!"

Muhammad: "Lie down so I can ride on you."

Umm Hanafi: "There's been enough riding. Pick some other game, by God. God… look at the jasmine and the hyacinth vines. Look at the pigeons."

Uthman: "You're as ugly as a water buffalo, and you stink."

Umm Hanafi: "May God forgive you. I've gotten sweaty chasing after you."

Uthman: "Let us see the well, if only for a moment."

Umiri Hanafi: "The well is full of jinn. That's why we closed it."

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma