- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Page 3

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Read online

Page 3

The day of his reception by the Pharoah brings another emotional experience Ahmose cannot let disempower him: the garden of the palace usurped by Apophis was his grandfather Pharoah Seqenenra's where in childhood he would play with Nefertari — now his wife, whom Mahfouz knows, in his skill at conveying the unstated merely by an image, he does not have to remark that Ahmose is betraying.

In the palace Apophis discards his crown and puts on his head the vanity of a fake, bejewelled double crown the merchant presents him with along with the gift of three pygmies. They are to amuse him; or to remind him of something apposite to His Majesty, in guise of quaint information. ‘They are people, my lord, whose tribes… believe that the world contains no other people than themselves.’ The scene of greedy pleasure and enacted sycophancy is blown apart by the charging in of Apophis's military commander Rukh, the man who brought Ebana to court accused of insulting him. He is drunk, raging, and demands a duel with the Nubian trader who paid gold to save her from flogging.

Ahmose is strung between choices: flee like a coward, or be killed and his mission for his people lost. He's aware of Princess Amenridis regarding him with interest. Is it this, we're left to decide, which makes him accept Rukh's challenge? As proof of manhood? For the public the duel is between class, race: the royal warrior and the peasant foreigner. Commander Rukh loses humiliatingly, incapacitated by a wounded hand. Whatever Ahmose's reckless reason in taking on the duel, his present mission is fulfilled; the deal — treasures to Pharoah Apophis in exchange for the grain and workers — is agreed. He may cross the border for trade whenever he wishes. Aboard his homeward ship in what should be triumph, Ahmose is asking himself in that other mortal conflict, between sexual love and political commitment: Is it possible for love and hate to have the same object?’ Amenridis is part of the illicit power of oppression. ‘However it be with me, I shall not set eyes upon her again…'

He does, almost at once. Rukh pursues him with warships, to duel again and ‘this time I shall kill you with my own hands'. Amenridis has followed on her ship, and endowed with every authority of rank, stops Rukh's men from murdering Ahmose when he has once again wounded Rukh. Ahmose asks what made her take upon herself ‘the inconvenience’ of saving his life. She answers in character: ‘To make you my debtor for it.’ But this is more than sharply aphoristic. If he is somehow to pay he must return to his creditor; her way of asking when she will see again the man she knows as Isfinis. And his declaration of love is made, he will return, ‘my lady, by this life of mine which belongs to you'.

His father Kamose refuses to allow him to return in the person of merchant Isfinis. He will go in his own person, Ahmose, only when ‘the day of struggle dawns'. Out of the silence of parting comes a letter. In the envelope is the chain of the green heart necklace. Amenridis writes she is saddened to inform him that a pygmy she has taken into her quarters as a pet has disappeared. ‘Is it possible for you to send me a new pygmy, one who knows how to be true?’ Mahfouz discards apparent sentimentality for startling evidence of deep feeling, just as he is able to dismantle melodrama with the harshness of genuine human confrontation. Desolate Ahmose: ‘She would, indeed, always see him as the inconstant pygmy.'

The moral ambiguity of a love is overwhelmed by the moral ambiguities darkening the shed blood of even a just war. The day of struggle comes bearing all this, and Kamose with Ahmose eventually leads the Theban army to victory, the kingdom is restored to the Thebes.

Mahfouz like Thomas Mann is master of irony, with its tugging undertow of loss. Apophis and his people, his daughter, have left Memphis in defeat. It is a beautiful evening of peace. Ahmose and his wife Nefertari are on the palace balcony, overlooking the Nile. His fingers are playing with a golden chain. She notices: ‘How lovely! But it's broken.’ ‘Yes. It has lost its heart.’ ‘What a pity!’ In her innocent naivety, she assumes the chain is for her. But he says, “I have put aside for you something more precious and more beautiful than that… Nefertari, I want you to call me Isfinis, for it's a name I love and I love those who love it.'

‘Are you still writing?’

People whose retirement from working life has a date, set as the date of birth and the date of death yet to come, ask this question of a writer. But there's no trade union decision bound upon writers; they leave practising the art of the word only when their ability to transform with it something of the mystery of human life, leaves them.

Yes, in old age Naguib Mahfouz was still writing. Still finding new literary modes to express the changing consciousness of succeeding eras with which his genius created this trilogy and his entire oeuvre, novels and stories. In the rising babble of our millennium, radio, television, mobile phone, his mode for the written word is distillation. In a recent work, The Dreams, short prose evocations drawing on the fragmentary power of the subconscious, he is the narrator walking aimlessly where suddenly ‘every step I take turns the street upside-down into a circus'. At first he ‘could soar with joy', but when the spectacle is repeated over and over from street to street, “I long in my soul to go back to my home… and trust that soon my relief will arrive'. He opens his door and finds — ‘the clown there to greet me, giggling'.[3] No escape from the world and the writer's innate compulsion to dredge from its confusion, meaning.

Nadine Gordimer

Select bibliography

This bibliography is confined to works available in English.

MEHAHEM MILSON, Naguib Matifouz: The Novelist-Philosopher of Cairo, St Martin Press, New York, 1998.

RASHEED EL-ENANY,Naguib Mahfouz: The Pursuit of Meaning, Routledge, London and New York, 1993.

MICHAEL BEARD and ADNAN HAYDAR, eds, Naguib Mahfouz: From Regional Fame to Global Recognition, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, 1993.

TREVOR LE GASSICK, ed., Critical Perspectives on Naguib Mahfouz, Three Continents Press, Washington DC, 1991.

HAIM GORDON,Naguib Mahfouz's Egypt: Existential Themes in his Writings, Greenwood Press, New York, 1990.

M. M. ENANi, ed., Egyptian Perspectives on Naguib Mahfouz: A Collection of Critical Essays, General Egyptian Book Organization, Cairo, 1989.

MATTITYAHU PELED,Religion My Own: The Literary Works of Najib Mah- fuz, Transaction Books, New Brunswick, 1983.

SASSON SOMEKH,The Changing Rhythm: A Study of Najib Mahfuz's Novels, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1973.

E. M. FORSTER,Alexandria: A History and a Guide, Whitehead Morris Limited, Alexandria, 1922.

MATTi MOOSA, The Origins of Modern Arabic Fiction, Three Continents Press, Washington, DC, 1983.

ALI B. JAD,Form and Technique in the Egyptian Novel fgis-igyi), Ithaca Press, London, 1983.

ROGER ALLEN,The Arabic Novel: An Historical and Critical Introduction, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, 1982.

HILARY KILPATRICK, The Modern Egyptian Novel: A Study in Social Criticism, Ithaca Press, London, 1974.

HAMDI SAKKUT,The Egyptian Novel and its Main Trends (1913–1952), The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 1971. j. BRUGMAN,An Introduction to the History of Modern Arabic Literature in Egypt, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1984.

CHARLES D. SMITH,Islam and the Search for Social Order in Modern Egypt: A Biography of Muhammad Husayn Haykal, State University of New York, Albany, 1983.

MARINA STAGH,The Limits of Freedom of Speech: Prose Literature and Prose Writers in Egypt under Nasser and Sadat, Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm, 1994.

H. A. R. GIBB,Arabic Literature, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1963. ALBERT HOURANi, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age: 1798–1939, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1962. p. j. VATiKiOTis, The History of Egypt, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1985.

Map of Ancient Egypt

Khufu's Wisdom

A Novel of Ancient Egypt

Translated by Raymond Stock

1

The possessor of Divine Grandeur and Lordly Awe, Khufu, son of Khnum, reclined on his gilded couch, on the balcony of the antechamber overlooking his lush and far-f

lung palace garden. This paradise was immortal Memphis herself, the City of the White Walls. Around him was a band of his sons and his closest friends. His silken cloak with its golden trim glistened in the rays of the sun, which had begun its journey to the western horizon. He sat calmly and serenely, his back resting on cushions stuffed with ostrich feathers, his elbow embedded in a pillow whose silk cover was striped with gold. The mark of his majesty showed in his lofty brow and elevated gaze, while his overwhelming power was displayed by his broad chest, bulging forearms, and his proud, aquiline nose. He bore all the dignity of his two-score years, and the glorious aura of Pharaoh.

His piercing eyes ran back and forth between his sons and his companions, before shifting leisurely forward, where the sun was setting behind the tops of the date palms. Or they would turn toward the right, where they beheld in the distance that eternal plateau whose eastern side fell under the watchful gaze of the Great Sphinx, and in whose center reposed the mortal remains of his forebears. The plateau's surface was covered with hundreds and thousands of human forms. They were leveling its sand dunes and splitting up its rocks, digging out the mighty base for Pharaoh's pyramid — which he wanted to make a wonder in the eyes of humankind that would endure for all the ages.

Pharaoh cherished these family gatherings, which refreshed him from his weighty official duties, and lifted from his back the burden of habitual obligations. In them he became a companionable father and affectionate friend, as he and those closest to him took refuge in gossip and casual conversation. They discussed subjects both trivial and important, trading humorous stories, settling sundry affairs, and determining people's destinies.

On that distant day, long enclosed in the folds of time — that the gods have decreed to be the start of our tale — the talk began with the subject of the pyramid that Khufu wanted to make his eternal abode, the resting place for his flesh and bones. Mirabu, the ingenious architect who had heaped the greatest honors on Egypt through his dazzling artistry, was explaining this stupendous project to his lord the king. He expounded at length on the vast dimensions desired for this timeless enterprise, whose planning and construction he oversaw. Listening for a while to his friend, Pharaoh remembered that ten years had passed since the start of this undertaking. Not hiding his irritation, he reminded the revered craftsman, “Aye, dear Mirabu, I do believe in your immense ingenuity. Yet how long will you keep me waiting? You never tire of telling me of this pyramid's awe-someness. Still, we have yet to see one layer of it actually built — though an entire decade has passed since I marshaled great masses of strong men to assist you, assembling for your benefit the finest technical resources of my great people. And for all of that, I have not seen a single trace on the face of the earth of the pyramid you promised me. To me it seems these mastaba tombs in which their owners still lie — and which cost them not a hundredth of what we have spent so far — are mocking the great effort we have expended, ridiculing as mere child's play our colossal project.”

Apprehension rumpled Mirabu's dusky brown face, wrinkles of embarrassment etching themselves across his broad brow. With his smooth, high-pitched voice, he replied, “My lord! May the gods forbid that I ever spend time wantonly or waste good work on a mere distraction. Indeed, I was fated to take up this responsibility. I have borne it faithfully since making it my covenant to create Pharaoh's perpetual place of burial — and to make it such a masterpiece that people will never forget the fabulous and miraculous things found in Egypt. We have not thrown these ten years away in play. Instead, during that time, we have accomplished things that giants and devils could not have done. Out of the bedrock we have hewn a watercourse that connects the Nile to the plateau upon which we are building the pyramid. Out of the mountains we have sheared towering blocks of stone, each one the size of a hillock, and made them like the most pliable putty, transporting them from the farthest south and north of the country. Look, my lord — behold the ships: how they travel up and down the river carrying the most enormous rocks, as though there were tall mountains moving along it, propelled by the spells of a monstrous magician. And look at the men all absorbed in their work: see how they proceed so slowly over the ground of the plateau, as though it were opening to reveal those it has embraced for thousands of years gone by!”

The king smiled ironically. “How amazing!” he said. “We commanded you to build a pyramid — and you have dug for us a river, instead! Do you think of your lord and master as a sovereign offish?”

Pharaoh laughed, and so did his companions — all but Prince Khafra, the heir apparent. He took the matter very seriously. Despite his youth, he was a stern tyrant, intensely cruel, who had inherited his father's sense of authority, but not his gracious-ness or amiability.

“The truth is that I am astounded by all those years that you have spent on simply preparing the site,” he berated the architect, “for I have learned that the sacred pyramid erected by King Sneferu took much less time than the eons you have wasted till now.”

Mirabu clasped his hand to his forehead, then answered with dejected courtesy, “Herein, Your Royal Highness, dwells an amazing mind, tireless in its turnings, ever leaning toward perfection. It is the fashioner of the ideal, and — after monumental effort — a gigantic imagination was created for me whose workings I expend my very soul in bringing to physical reality. So please be patient, Your Majesty, and bear with me also, Your Royal Highness!”

There was a moment of silence. Suddenly the air was filled with the music of the Great House Guards, which preceded the troops as they retired to their barracks from the place where they had been standing watch. Pharaoh was thinking about what Mirabu had said, and — as the sounds of the music melted away — he looked at his vizier Hemiunu, high priest of the temple of Ptah, supreme god of Memphis. He asked — with the sublime smile that never left his lips, “Is patience among a king's qualities, Hemiunu?”

Tugging at his beard, the man answered quietly, “My lord, our immortal philosopher Kagemni, vizier to King Huni, says that patience is man's refuge in times of despair, and his armor against misfortunes.”

“That is what says Kagemni, vizier to King Huni,” said Pharaoh, chuckling. “But I want to know what Hemiunu, vizier to King Khufu, has to say.”

The formidable minister's cogitation was obvious as he prepared his riposte. But Prince Khafra was not one to ponder too cautiously before he spoke. With all the passion of a twenty-year-old born to royal privilege, he declared, “My lord, patience is a virtue, as the sage Kagemni has said. But it is a virtue unbecoming of kings. Patience allows ministers and obedient subjects to bear great tribulations — but the greatness of kings is in overcoming calamities, not enduring them. For this reason, the gods have compensated them for their want of patience with an abundance of power.”

Pharaoh tensed in his seat, his eyes glinting with an obscure luminescence that — were it not for the smile drawn upon his lips — would have meant the end for Mirabu. He sat for a while recalling his past, regarding it in the light of this particular trait. Then he spoke with an ardent fervor that, despite his forty years, was like that of a youth of twenty.

“How beautiful is your speech, my son — how happy it makes me!” he said. “Truly, power is a virtue not only for kings, but for all people, if only they knew it. Once I was but a little prince ruling over a single province — then I was made King of Kings of Egypt. And what brought me from being a prince into possession of the throne and of kingship was nothing but power. The covetous, the rebellious, and the resentful never ceased searching for domains to wrest away from me, nor in preparing to dispatch me to my fate. And what cut out their tongues, and what chopped off their hands, and what took their wind away from them — was nothing but power. Once the Nubians snapped the stick of obedience — when ignorance, rebellion, and impudence put foolish ideas into their heads. And what cracked their bravura to compel their submission, if not power? And what raised me up to my divine status? And what made my word the law of the land, an

d what taught me the wisdom of the gods, and made it a sacred duty to obey me? Was it not power that did all this?”

The artist Mirabu hastened to interrupt, as though completing the king's thought, “And divinity, my lord.”

Pharaoh shook his head scornfully. ‘And what is divinity, Mirabu?” he asked. ‘“Tis nothing if not power.”

But the architect said, in a trusting, confident tone, “And mercy and affection, sire.”

Pointing at the architect, the king replied, “This is how you artists are! You tame the intractable stones — and yet your hearts are more pliant than the morning breeze. But rather than argue with you, I'd like to throw you a question whose answer will end our meeting today. Mirabu, for ten years you have been mingling with those armies of muscular laborers. By now you must truly have penetrated their innermost secrets and learned what they talk about among themselves. So what do you think makes them obey me and withstand the terrors of this arduous work? Tell me the honest truth, Mirabu.”

The architect paused to consider for a moment, summoning his memories. All eyes were fixed upon him with extreme interest. Then, with deliberate slowness, speaking in his natural manner — which was filled with passion and self-possession — he answered, “The workers, my lord, are divided into two camps. The first of these consists of the prisoners of war and the foreign settlers. These know not what they are about: they go and they come without any higher feelings, just as the bull pushes around the water wheel without reflection. If it weren't for the harshness of the rod and the vigilance of our soldiers, we would have no effect on them.

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

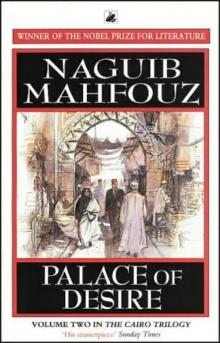

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma