- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

The Mirage Page 3

The Mirage Read online

Page 3

That era is long gone now, but it still lives in my heart and flows in my blood. It was this that placed fear at the center of my soul, turning it into the hub around which my entire life revolved. In so doing, it destroyed my peace of mind and cast me into a state of unrelenting misery. I was nothing but a frightened spirit that, if it weren’t confined to a body, would flee in terror. I was afraid of people. I was afraid of animals and insects. I was afraid of the dark and the chimeras that stalked me there. I would have done anything to avoid being alone with a cat, and never in a million years would I have slept in a room by myself. Even so, fear ran deeper in my life than the things through which it manifested itself to me. Its long, thick shadow loomed over the past, the present, and the future, wakefulness and sleep, my way of life and its philosophy, sickness and health, love and hatred. It left nothing untouched. I lived most of my past life heedless and ignorant, not knowing the reason for my misery. Ordeals and afflictions later clarified certain aspects of my life to me, rending with their harshness the veils that had kept my distressing secrets concealed. Still, my sense of helplessness hasn’t left me. It’s a sense that rests, in truth, on my inadequate education and sophistication and a lack of confidence in my mental powers. My mother was the source of these torments. Yet, she was also my sole refuge from them, and I repaired to the shelter she offered without hesitation.

Among the memories I carry from that unforgettable era are the times when we—my mother and I—would stand beside my grandmother’s grave during certain seasons, crowning it with basil and reciting the Fatiha as we called down divine mercy upon her. We would talk often about the grave and those in the grave. How do they sleep? How are they received? What do they face by way of affliction and divine judgment? How do verses from the Holy Qur’an descend upon them as light that drives away their forlornness and gloom and alleviates their sense of isolation? Since it was my grandmother’s grave, I loved it intensely. When my mother wasn’t looking, I would rush over to one side of it and plunge my fingernails into its soil, then dig with a fury in the hope of catching a glimpse of the unknown that lay buried under the ground. It would distress me no end to hear her repeating, “To God do we belong, and to Him shall we return,” or, “To dust shall we return,” or, “Death is the final end of everything that lives.”

Once I asked her in astonishment, “Are we all going to die?”

Vexed by my question, she tried to distract me from it, but I refused to let it go.

“After a long life, God willing,” she said.

Eyeing her fearfully, I asked again, “And you, Mama?”

“Of course,” she replied, concealing a smile. “I’ll die some day.”

Pained by her words, I cried, “No! No! You’ll never die!”

She patted me affectionately on the head and said soothingly, “Pray for me to have a long life, and I’ll pray for the Most Merciful and Compassionate One to answer your prayer.”

So, holding my two little palms heavenward, I prayed to God from the depths of my heart, my eyes filled with tears.

5

Was I going to stay in her lap forever, as though I were part of her body?

I was all of four years old, and the time had come for me to want to play and have friends. I had nowhere to escape to in the house except the balcony, which overlooked the courtyard and the street beyond. The children of the family that occupied the first floor would play in the courtyard, and I would look wistfully down at them. Sometimes they’d look back up at me with an unspoken invitation in their eyes that shook me from head to toe, and one day I asked my mother’s permission to join them.

“What’s happened to your mind?” she asked me in alarm. “Don’t you see that they fight all the time? What would I do if they hit you or hurt you? Or if they took you out to the street where cars are passing by all the time? What will you learn from them but mischief and bad manners? As for me, I tell you stories, and if you want to, we go out together to visit Sayyida Zaynab. If you really love me, don’t leave me.”

Seeing the look of exasperation and resentment on my face, she continued, “I’ve been deprived of seeing your sister and brother, so you’re all I have left in the world. And now you want to leave me. May God forgive you!”

“I love you more than anything in the world,” I said, “but I want to play!”

However, she wasn’t about to give in to this desire of mine. When I found myself at my wits’ end over her unrelenting stance, I would cry or throw temper tantrums, pulling my hair and ripping my clothes. But there was nothing in the world that would have caused her to yield to my desire to distance myself from her. Apart from this one thing, however, she spared no effort to please me. She would buy me toys of all shapes and kinds, and when she sensed that I was cross or bored, she would invite one of the neighbor children to play with me under her watchful eye. But none of this was sufficient to satisfy my thirst for freedom. One day, taking advantage of a moment of inattentiveness on her part, I managed to slip out of the flat. As I fled, I was beside myself with joy, and I was received by the children in the courtyard with an incredulous welcome. Although we were somewhat acquainted with one another, I still didn’t know how to approach them. I stood glued to my place, flustered and shy. It wasn’t long before my mother looked down from the balcony and called to me in a sharp, angry voice. But the oldest of the children came up to me and invited me to play, saying, “Don’t pay any attention to her!” And for the first time in my life, I ignored what she was saying. I rushed forward into the circle of players and took my place with delight beyond measure. However, hardly had a few minutes passed before an argument broke out between me and one of the other children, and he slapped me in the face. I was stupefied, as it may have been the first time I’d ever been slapped in my life. I threw myself on his arm and plunged my teeth into it, whereupon, without hesitation, his friends fell upon me with blows and kicks. My mother shouted at them with angry threats, but they didn’t leave me alone until she’d threatened to throw a pitcher at them. By the time they’d finished with me, I was in a pitiful state indeed, panting and teary-eyed. She called me to come up to her but I was overcome with shame and embarrassment, so I stood there with downcast eyes as if I were pinned to the ground and made no move to answer her call. In fact, I didn’t budge until the gatekeeper came and carried me up to her, whereupon she washed my face and legs for me.

“It serves you right! It serves you right!” she said in an agitated tone. “This is what happens to people who disobey their mothers. God will forgive us for anything except defying our mothers. This is what it’s like to play with other children. So, how was it?”

I wasn’t pained by the beating half as much as I was by my defeat before her. Lying, I assured her that I’d been the one at fault, and that I was the one who had attacked the other boy first.

I found it strange that my mother herself didn’t mix with people very much, and that we rarely received visitors in our house. Vexed by her isolation, my grandfather would urge her constantly to spend more time with people as a way of cheering herself up. Then God Himself decided to send her some company: my mother’s sister and her family came to stay as guests at our house. My aunt lived with her husband, who worked as an Arabic teacher in Mansoura, and they’d come to Cairo to spend a month of their summer vacation at our house. Suddenly I found myself in the midst of six boys and a girl, and despite my mother’s best efforts, things slipped out of her control. The eldest of the boys was ten while the youngest was still crawling. The quiet house was transformed into a circus hopping with monkeys and other wild creatures. I frisked and frolicked till I was nearly delirious with joy. We played al-gadeed, hopscotch, choo-choo train, and hide-and-go-seek.

When we got tired of being in the house, we’d take off for the street, and I could hardly believe my good fortune. My mother wanted to prevent me from going out with them, but my aunt would object, saying, “Let him play with the other children, Sister! Even if he were a girl, it

wouldn’t be right for you to confine her too soon!”

The two sisters had distinctive temperaments despite the many ways in which they were similar. My aunt was exceedingly plump and was the cheerful sort that likes to joke and laugh. She didn’t cause herself misery by worrying unduly about her children, and when my grandfather left the house, she would sing with a lovely voice in imitation of Munira al-Mahdiya. As for my mother, she seemed to be the very opposite of her sister. She was thin, reclusive, full of fears and worries, and almost abnormally attentive and affectionate. The circumstances of her life had frayed her nerves, and the minute she found herself alone, she’d be engulfed by a cloud of melancholy. She may not have been entirely pleased that her sister stayed with us that month, not due to any lack of affection toward her but, rather, because her sister’s children had monopolized my time and attention, thereby spoiling my undivided allegiance to her. Once she complained to my aunt of her fear that I might be hurt while playing in the street. My aunt just laughed nonchalantly and, in a slightly reproachful tone, said to her, “So is your son flesh and blood while mine are made of steel? Be strong and have more trust in God!”

As for me, so overwhelming was my bliss that I forgot all my mother’s instructions. I gave myself over to fun and enjoyment for that entire month, which had broken in on my monotonous life like a happy dream. I flung myself into the arms of diversion the way a starving man falls upon a long-awaited meal, and not for a single moment did I feel bored or tired. When we came back to the house at night, I would put my uncle’s turban on my head, mimic the way he talked, and burp the way he burped. Following the burp I would mutter, “Oh, pardon me, please!” to the delighted laughter of everyone around me.

That month was like a dream. But dreams don’t last, and like a dream, it came to an end. I found myself looking on dolefully as bags were packed and piled up near the door in preparation for their departure. Then the time came for the inevitable parting with its embraces and goodbyes. The carriage picked them up and bore them away as I bade them farewell from the balcony, tearful and disconsolate.

My mother said to me, “That’s enough playing and running around in the street for you. Settle down now and go back to the way you were before, when you didn’t leave me and I didn’t leave you.”

I listened to her in silence. I loved her with all my heart, but I also had a yen to play and have fun. Some time after this my mother brought us a young servant girl whom she allowed to play with me under her supervision. She was better than no playmate at all, at least. She was a homely girl, but she was better for me than the aging chef and old Umm Zaynab.

My mother performed her prayers regularly. I began imitating her when she prayed, and it seems she saw in this a fitting opportunity to teach me the principles of our religion as she understood it. She started out by teaching me about heaven and hell, thereby adding new words to my vocabulary of fear. This time, however, they were accompanied by sincere emotion, love, and faith.

6

This state of affairs between my mother and me led to a delay in my school enrollment. I got to be nearly seven years old without having received the least bit of education. Finally, though, my grandfather intervened. He called me one day as he sat on the porch on that long seat of his that rocked back and forth. He tweaked my ear playfully, then said to me, “For a long time you’ve wanted to be able to join other boys your age. Well, now God has set you free, and we’re going to let you share their life for a long, long time. You’re going to school!”

I listened to him in bewilderment at first, since I didn’t know a thing about school. Then, realizing that he was granting me my freedom, I looked at my mother questioningly, not knowing whether to believe him or not. And great was my amazement when I saw her smile at me encouragingly with a look of acquiescence on her face.

Nearly bursting with joy, I asked my grandfather excitedly, “Will I play at school like the other children?”

“Of course, of course,” replied the old man with a nod of his hoary head. “You’ll play a lot and learn a lot. Then later you’ll become an officer like me.”

“When will I go?” I asked impatiently.

“Very soon,” he said with a smile. “I’ll register you tomorrow.”

Autumn was upon us, and the next morning they dressed me up in a suit, a fez, and new shoes, which brought back happy memories of the holiday. My grandfather took me to Atfat Qasim, which wasn’t far from our house. We went into the second building we came to on the left, which was Roda National Primary School. The school, which had been chosen due to its proximity to our house, consisted of a medium-sized courtyard and a one-story building with three rooms: two classrooms and the principal’s office. The principal—who was also the owner of the school—received my grandfather respectfully and even reverently, and in his presence he treated me with kindness, complimenting me on my cleanliness and my new clothes. Consequently, I felt friendly toward him and expected good things from him in the future. Within minutes, I’d been enrolled along with the other students in the school. My grandfather paid the fees, and we headed home.

As we left the school my grandfather said to me, “Now you’ll be an excellent pupil! School will start next Saturday.”

My mother announced her satisfaction with the new development. However, she wasn’t able to conceal the melancholy she felt. Seeing this, my grandfather was annoyed with her and said to her somewhat sharply, “What will you do if, once he’s seven years old, his father reclaims him?”

“Over my dead body!” she cried, gaping at my grandfather with horror and anguish.

On the appointed Saturday, my grandfather took me to school, then returned home. As he was about to take leave of me I clung to his hand, feeling a sudden pang of fear that caused me to forget how I’d longed for this very moment. I even suggested that he take me back home with him, but he simply laughed that resounding laugh of his and, pointing to the other pupils, said, “Meet your new family!”

I stood near the door feeling more flustered than I’d ever felt in my life, and a feeling of regret came over me. Looking timidly and apprehensively at the pupils scattered about the courtyard, I hoped no one would notice me. But my smart new clothes caught people’s attention, and I lowered my gaze feeling agonizingly shy. How long will this torture go on? I wondered.

However, a boy came up and greeted me, then stood with me as though we were friends. Then he asked me for no apparent reason, “Did your father bring you?”

Since I considered my grandfather both a grandfather and a father, I nodded in the affirmative.

“What does he do?” he asked, “and what’s his name?”

Even though conversation was a cause of distress for me, I still welcomed this question in particular, and replied proudly, “Colonel Abdulla Bey Hasan.”

The boy told me that his father was So-and-so Bey too, though I’ve forgotten his name now. Then, as though he’d grown weary of my quiet, stuffy manner, he left me and went to join some other buddies. Feeling lonelier than ever, I wondered: Will I be able to fit in with these boys? Will I really be able to play with them, or will the disaster that befell me in our courtyard at home be repeated here too? My heart was gripped with fear, and if I’d had the courage to retreat and go home on the spot, I would have. Then the bell rang, delivering me from my thoughts, whereupon they stood us in a line and brought us into the classroom. It hadn’t occurred to me up to that point that school was anything but a huge playground. However, when I sat down at one of the school desks and the elderly teacher began the new school year with the traditional instructions having to do with maintaining order and not moving around or talking in class, I was certain that what I’d entered was nothing less than a prison. Perplexed and disturbed, I thought: Did my grandfather make a mistake, or did they deceive him? My imagination went soaring home, where I pictured my mother sitting alone. Do you suppose she’s forgotten me? I wondered. At around this time she’ll be overseeing Umm Zaynab as she sweeps the r

ooms and dusts the furniture. Hasn’t she thought about me? Can she bear to part with me for the entire day?

When the first lesson ended, I hadn’t heard a word the teacher said. And it was no wonder, since I’d decided that this first day would also be my last. During recess I saw the principal passing by the classroom door, and I breathed a sigh of relief. Not having forgotten the kindness he’d shown me when I came to enroll with my grandfather, I approached him without hesitation. As I came up to him timidly, he turned toward me with an uncomprehending look on his face. Then he cast me a harsh, quizzical gaze, and I thought he’d forgotten who I was.

In a voice that was barely audible I said, “I’m Colonel Abdulla Bey Hasan’s son.”

“And what do you want?” he asked in astonishment.

Gathering up my courage, I said, “I want to go home.”

“Get back to your desk, damn you!” he thundered in my face.

Stunned by his shouting, I returned to my place, nearly swooning from fright and anguish. From that moment onward, I stayed put, terrorized and distraught. As the day dragged on I started to feel I needed to go to the bathroom, but I was so afraid, I held it in. Not once did I think of asking the teacher for permission to leave the class. Even during recess, I was so apprehensive, I couldn’t bring myself to ask someone to show me where the toilet was. I started fidgeting and writhing like someone who’s been stung, pressing my knees together in torment and anguish. The time passed heavily and miserably until, when the bell rang at last, I took off as fast as my legs would carry me. I reached the house in a matter of seconds and ascended the stairs in leaps and bounds. In the flat I found my mother waiting for me, and when she saw me she exclaimed, “Welcome, light of my eyes!”

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

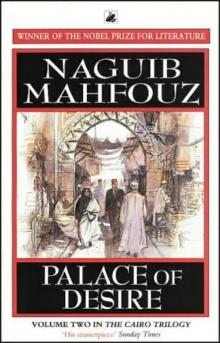

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma