- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

Karnak Café Page 5

Karnak Café Read online

Page 5

“But there is one thing that I need to tell you: when suffering pushes someone too far, he can still get the better of it. Even in moments of the direst possible agony, he can still leap up and express his concerns with a level of recklessness that can be regarded as a sign of either despair or power—both are equally valid.

“So I surrendered myself to the fates and decided to allow the very devil himself to come if that was indeed what destiny had determined was to be my lot, or even death if it came to that. I stopped posing myself questions for which there were no answers, but made up my mind to take the lead from the way influenza behaves, countering antibiotics by creating whole new generations of bacteria that are resistant to medicine.”

“Did you stay on your feet for a long time?” I asked.

“When the strain of it all really got to me,” he said, “I squatted and then sat cross-legged on the floor. I slept as much as I could. Can you imagine? When I woke up, I remembered where I was. I realized that I had completely lost all sense of time. What time was it when I had fallen asleep? Was it daytime or night now? I felt my chin and decided to use its growth as a very inaccurate timepiece.”

“Did they leave you there for long?”

“Yes.”

“How about food?”

“The door used to open, and a tray would be pushed inside with some cheese on it, or else something salty with bread.”

“What about the toilet?”

“At a specific time each day, the door would open again, and a giant man the size of a circus wrestler would call me outside and take me to the latrine at the end of the corridor. As I followed him, I would have to keep my eyes almost closed because the light was so bright. I had hardly closed the door behind me before he would start yelling, ‘Get a move on, you son of a bitch! Do you think you can stay in there all day, you bastard?’ I’ll leave you to imagine how I was managing inside.”

“Have you any idea how long you were there?”

“God alone knows. My beard grew so long, I couldn’t tell any more.”

“But they cross-examined you, for sure?”

“Oh yes,” he replied with a frown. “There came the day when I found myself standing in front of Khalid Safwan.”

For a moment he was silent, his eyes narrowing with the sheer emotion aroused by the memory. Inevitably I now felt myself being drawn into the intense feelings he was experiencing.

“There I stood in front of his desk, barefoot and wearing only a shoddy nightshirt. My nerves were completely shot. Behind me stood one person, or maybe more. I was not allowed to look either right or left, let alone behind me. For that reason I couldn’t tell where I was and had to stare blearily straight at him. Whatever vestiges of my humanity may have been left at this point dissolved in an all-encompassing sense of terror.”

For just a moment his expression was etched with suppressed anger. “In spite of everything that happened,” he went on, “his image is indelibly recorded deep inside me. Of medium height, he had a large, elongated face with bushy eyebrows that pointed upwards. He had big, sunken eyes and a broad, prominent forehead. His jaw was strong, but he managed to keep his expression totally neutral. I can vividly recall all those details. Even so, I was feeling so utterly desperate that I managed to create an illusion of hope for myself concerning his role.

“ ‘Thank God!’ I said. ‘At last, I find myself standing before someone with authority.’

“A sharp cuff from behind cut me off, and I let out a groan of pain.

“ ‘Only speak when you’re asked a question,’ he said.

“He proceeded to ask me for my name, age, and profession, all of which I answered.

“ ‘When did you join the Muslim Brothers?’ he asked.

“The question astonished me. Now I realized for the first time what it was they were accusing me of being. ‘Never for a single moment have I belonged to the Muslim Brotherhood,’ I replied.

“ ‘What’s the beard for then?’

“ ‘I’ve grown it in prison.’

“ ‘Are you suggesting that you haven’t been well treated here?’

“ ‘My dear sir,’ I replied in a tone that was tantamount to an appeal for help, ‘the treatment I have received here has been appalling and utterly unjustified.’

“ ‘God forbid!’

“I realized at once that I had just made a dreadful mistake, but it was too late.

“ ‘So,’ he asked again, ‘when did you join the Muslim Brotherhood?’

“ ‘I never …,’ I started to reply but never finished the sentence. I started falling to the floor in a crumpled mass; it rushed up to greet me in a manner that seemed almost magical. Khalid Safwan soon disappeared into the gloom. Later on, Hilmi Hamada told me that one of the devils standing behind me had hit me so hard that I fainted. When I came to, I was back in the same place they had taken me from—on the asphalt floor in the cell.”

“What an ordeal!” I said.

“Yes, it was,” he replied. “The whole thing ended suddenly and unexpectedly. What’s more, it was actually in Khalid Safwan’s own room.”

“ ‘We now have proof,’ he told me as soon as they brought me in, ‘that your name was recorded on a list because you had donated a piaster to build a mosque. You never had an actual connection with them.’

“ ‘Isn’t that exactly what I’ve been telling you?’ I asked in a voice quivering with emotion.

“ ‘It’s an excusable error,’ he replied. ‘But contempt for the revolution is inexcusable.’ With that he proceeded to deliver his lecture with the greatest conviction. ‘We are here to protect the state that manages to keep you free of all kinds of subservience.’

“ ‘I am one of its loyal children.’

“ ‘Just look on the time you have spent here as a period of hospitality. Always remember how well you were treated. I trust that you’ll always remember that. Just bear in mind the fact that scores of people have been laboring night and day in order to prove your innocence.’

“ ‘I thank both God and you, sir.’ ”

The sheer memory of that moment led Isma‘il al-Shaykh to let out a bitter laugh.

“Were other people arrested for the same reason?” I asked.

“There were in fact two members of the Muslim Brothers in our group,” he replied. “They interrogated Zaynab and learned of her relationship with me, so they released her as well. It was because of us that they had arrested Hilmi. When they discovered that I was innocent, they did the same for him too.”

It was all a very bitter experience for him. As a result he had come to totally distrust a government agency, namely the secret police. In spite of that, his belief in the state itself and the revolution remained rock-solid and unshaken; neither doubt nor corruption could alter his opinion on that score. As far as he was concerned, the secret police were using techniques of their own devising, but the people in authority remained in the dark.

“When I was released,” Isma‘il said, “I thought about complaining to the government authorities, but Hilmi Hamada used every argument he could to stop me.”

“He obviously didn’t believe in the very state itself, wouldn’t you say?”

“Yes.”

After the dreadful defeat of June 1967, Isma‘il set himself to study modern Egyptian history for the first time.

“I have to tell you,” he said, “that I’ve been constantly surprised by the power and freedom that the opposition always had and also by the role played by the Egyptian judiciary. It wasn’t a period of undiluted evil. Quite the contrary, there was a whole series of intellectual trends that deserved to continue, and indeed to grow and flourish. It is the very fact that such features have been systematically overlooked that has contributed to our defeat.”

Next he told me about his second period in prison.

“I was visiting Hilmi Hamada’s house,” he told me. “I left at around midnight, and they arrested me on the spot. With that I found myself back in the

dark and empty void.”

Once again he found himself forced to ponder what the accusation might be this time. He had a long time to wait before he was to find out, and once again he went through all the tortures of hell. There he was yet again facing Khalid Safwan.

“I stood there silently,” he told me. “This time I could benefit from my previous experience. Even so, I was still expecting trouble from all the same directions as before.

“ ‘You cunning little bastard,’ Khalid Safwan said, looking me straight in the eye. ‘Here we were, thinking you belonged to the Muslim Brothers.…’

“ ‘And I turned out to be innocent,’ I replied emphatically.

“ ‘But what was lurking just below the surface was even worse!’

“ ‘I believe in the revolution,’ I said fervently. ‘That’s the only true fact there is.…’

“ ‘Oh, everyone believes in the revolution,’ he said sarcastically. ‘In this very room, feudalists, Wafdists, and Communists have all avowed their belief in the revolution!’ He gave me a cruel stare. ‘So when did you join the Communists?’

“A denial was immediately on my lips, but I suppressed it. In a purely reflex action I raised my shoulders as though to hide my neck, but said nothing.

“ ‘When did you join the Communists?’ he repeated.

“I felt as though my neck were becoming increasingly constricted. I had no idea what to say, so I said nothing.

“ ‘Don’t you want to confess?’

“I remained silent, using it in much the same way as I had adopted misery inside that dark prison cell.

“ ‘Okay!’ he said.

“He gestured with his hand. I heard the sound of footsteps approaching, and my body gave a shudder. All of a sudden I became aware that someone was standing right beside me; out of the corner of my eye I could make out that she was a woman. I turned toward her in amazement. All the terror I was feeling was completely obliterated by another sensation. ‘Zaynab!’ I yelled, unable to stop myself.

“ ‘So you know this woman, do you?’ he asked. ‘It seems to matter to you what happens to her.’ He looked back and forth between the two of us with those sunken eyes of his. ‘Does it matter?’

“For an entire minute I felt utterly shattered.

“ ‘You’re an educated man, and I’m sure you’ve some imagination,’ he went on. ‘Can you imagine what might happen to this poor innocent girl if you refuse to talk?’

“ ‘What is it you want, sir?’ I asked in a mournful tone that was actually addressed to the world as a whole.

“ ‘I am still asking you the same question: when did you join the Communists?’

“ ‘I don’t remember the exact date,’ I replied, thereby burying any last flicker of hope, ‘but I confess to being a Communist.’

“My confession was recorded on a sheet of paper, and I was taken away.”

He was taken back to his cell. Contrary to his initial expectations, he was not tortured any more. Even so, he was convinced that now he was lost.

An unspecified amount of time went by, then one day a guard came along and took him to a locked door. “Perhaps you’d like to see your friend, Hilmi Hamada,” he said.

He removed the cover from the peephole and ordered Isma‘il to take a look inside.

“I looked inside. What I saw was so grotesque that at first I couldn’t take it all in. It was just like some surrealist painting. What I could make out was that Hilmi Hamada was hanging by his feet, silent and motionless; either he had passed out or else he was dead.

“I was so shocked and disgusted that I staggered backwards. ‘That is in …,’ I started to say but then the words stuck in my mouth as I noticed the guard staring at me.

“ ‘What were you saying?’ he asked.

“I felt utterly sick.

“ ‘This is in—,’ you said, ‘in … what?’

“He pushed me ahead of him. ‘Inhumane, is that what you meant?’ he asked. ‘And what about all those blood-filled dreams you all had, were they supposed to be so humane?’ ”

This was followed by a further interval of time during the course of which he had suffered a bad attack of influenza in the wake of a particularly cold spell of weather. While he was still recovering, he was summoned to Khalid Safwan’s office again. At that particular juncture his greatest desire was to be transferred to any other prison or jail. As it turned out, Khalid Safwan spoke first.

“ ‘You’re in luck,’ he said.

“I looked at him in amazement.

“ ‘Once again you’ve been proved innocent.’

“All my resources of strength deserted me, and I felt an overwhelming desire to sleep.

“ ‘Your visit to Hilmi Hamada’s house was entirely innocent, wasn’t it?’

“I was terrified and had no idea what to say.

“ ‘He’s confessed, but luckily for him too we’ve proof that he never joined any organization or party. It’s the real workers we’re after, not the amateurs.’

“With that my hopes of being released perked up again.

“ ‘You’re still not saying anything,’ he continued, ‘out of respect for the sanctity of friendship, no doubt.’ For a moment he just sat there, but then he went on, ‘It’s that same faith in the power of friendship that makes us want to be your friends as well.’

“When was he going to order my release? I wondered.

“ ‘Be a friend of ours,’ he said. ‘You told us you were devoted to the revolution. I believe you. So why don’t you be one of our friends? How do you like the idea?’

“ ‘I’m delighted, sir.’

“ ‘We’re all children of the same revolution. We’re honor-bound to protect it with all due vigor, isn’t that so?’

“ ‘Of course.’

“ ‘But there has to be a positive attitude as well. The friendship we require has to be a positive one.’

“ ‘I’ve regarded myself as a friend of the revolution from the very beginning.’

“ ‘So how would you feel if you learned that the revolution was being threatened? Would that make you happy? Would you keep your mouth shut about it?’

“ ‘Certainly not!’

“ ‘That’s exactly what we’re asking for. You’ll be going to see a colleague of ours who’ll tell you the proper way to do things. But I’d like to remind you that we’re a force that is in complete control of things. There are no secrets from us. Friends are rewarded, and traitors are punished. That’s the way it is.’ ”

Isma‘il’s face clouded over as he recalled this particular incident. If anything, he now looked even more miserable than before.

“Could you have said no?” I asked, trying to relieve his misery a bit.

“You can always find some excuse or other,” he said, “but there’s no point.”

So that is the way he emerged from his imprisonment, an informer with a fixed salary and a tortured conscience. However hard he struggled with himself to conceptualize his new job in terms of his strong ties to the revolution, he always ended up feeling utterly appalled at what he was doing.

“When I met Zaynab again,” he said, “for the first time ever I felt like some kind of stranger. Now I had a private life of my own about which she neither knew nor was supposed to know anything.”

“So you kept it from her, did you?”

“Yes. I was following direct orders.”

“Did you really believe they had that much authority over you?”

“Absolutely! I certainly believed it. You can add to the equation the terror factor that had totally destroyed my spirit, and also my own profound sense of shame. I couldn’t manage to convince myself that honor meant anything any more. I had to act in a totally reckless manner, and that was no easy matter when you consider not only my moral make-up but also my spiritual integrity. I started meandering around in never-ending torment. What made it that much worse was that, as far as I was concerned, Zaynab was a changed person too. She seemed to be ove

rwhelmed by a profound sense of grief; the way she kept behaving provided no clue as to how she was going to get out of it. That made me feel even more of a stranger to her.”

“But that was all to be expected, wasn’t it?” I commented. “Things would have improved eventually.”

“But I never caught even a glimpse of the Zaynab I had once known. She had always been so happy and lively; I thought nothing could ever dampen her spirit. But something had. I tried offering her encouragement, but one day she stunned me by saying that I was the one who needed encouraging!”

The week after Isma‘il had been released, something absolutely incredible had happened. They had left the college grounds and were walking together.

“Where are you going now?” she asked.

“To the Karnak Café for an hour or so, then I’ll go home.”

“I’d like to walk alone with you for a while,” she said, almost as though she were talking to herself.

He imagined that she had a secret she wanted to share with him. “Let’s go to the zoo, then,” he suggested.

“I want it to be somewhere safe.”

Hilmi Hamada solved the problem for them both by inviting them up to Qurunfula’s apartment (which was his as well). He left the two of them alone.

“Qurunfula will get the impression we’re up to something,” he said in a tone of innocent concern.

“Let her say what she likes!” replied Zaynab disdainfully.

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

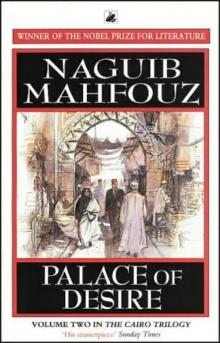

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma