- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

The Quarter Page 5

The Quarter Read online

Page 5

‘No, it didn’t seem to bother him.’

‘Why didn’t you reveal what fate was keeping hidden?’

‘We can never cross that line. Or else we lose the blessing!’

‘Then what happened?’

‘The singer of love songs vanished, and Sitt Badriyya, the rich old merchant’s wife went with him. The man was left with a one-year-old baby. The episode astounded the entire quarter, and our august merchant dropped dead.’

For a few moments there was silence.

‘Perhaps the man and woman will both be dead,’ the Head of the Quarter said, ‘before the young boy can get his revenge.’

‘God is all-knowing.’

‘So what is the meaning of the clouds you mentioned to the grandmother?’

‘It means that our knowledge involves uncertainty and temptation. But we should leave it to all-knowing God.’

OUR FATHER IGWA

All throughout his life his friends and peers had died; he was left with no friends or colleagues. This was Igwa, the lance-maker. His sons had died too, except for Anwar who was over eighty. The two of them shared the old house not far from the cellar. For a long time, they had not exchanged a single word; they simply stared at each other in silence, like strangers. However, the son had a problem with his legs. Needing to take a walk every few days, he had to have someone to lean on. So his father would come, give him his arm, and take him for a walk from the cellar to the fountain. All the while, people looked on in amazement.

Even so, time managed to devour his flesh, his fat, his teeth, and three-quarters of his sight and hearing. He could still eat, chew, and bring a smile to people’s faces; and sometimes wrath and anger too.

‘Someone who, by living so long, eats his way through all youth’s deadlines!’

The day of the auction to sell off the endowments’ ruined property was a day to remember.

It began with an attack of sickness that kept his son, Anwar, confined to bed.

People attending the auction were surprised when Igwa, the lance-maker, showed up carrying a small suitcase.

The Head of the Quarter, who was bidding for the land, stared at him in astonishment. He could not help himself.

‘Wouldn’t it be better,’ he asked Igwa, ‘if you stayed with your sick son?’

‘I’ve left him in the care of someone whose attention makes any other need redundant,’ was Igwa’s firm reply.

‘Why don’t you leave the land to someone else?’ the Head of the Quarter asked angrily. ‘Then he will profit from it as well as other people.’

‘Tomorrow I’m coming to an agreement with a building contractor,’ Igwa said. ‘Before a year’s over, I will profit from it and so will other people.’

THE STORM

It all happened when the sun was high in the sky. The day was temperate and calm.

‘My heart keeps warning me,’ said Sheikh Bahiyya, for no particular reason, ‘something sinister’s about to happen.’

At that moment we heard a soft whining, which kept up without pausing for breath. Gathering energy, it rose and fell, but then became stronger and stronger, an increasingly violent dust storm that whistled through every nook and cranny, its echoes sounding like animals howling.

More than one voice shouted: ‘O God, your forgiveness and mercy!’

However, now it was a roaring hurricane, bringing with it dust and different colours, to which everything rapidly succumbed. Containers, cages, and chickens flew off roofs, doors and windows slammed, screams and tears mingled. Meows, barks and brays all blended into one. With every passing minute, the chaos intensified and spread.

Voices escaped their usual confines:

‘This must be Judgment Day.’

‘We won’t find any houses left standing.’

‘This is how Satan reveals his secrets.’

The elemental violence continued until everyone was petrified and convinced that the end was undoubtedly near. Panic gripped the Head of the Quarter’s mind and heart. In order to satisfy himself that he was doing his job properly, he started shouting instructions that were lost in the raging noise:

‘Close your shops! Close doors and windows! No one should stay in the street!’

He made his way to the mosque courtyard and exchanged a despairing look with the Imam.

‘What are you going to do, Head of the Quarter?’ one of the refugees in the mosque asked him.

‘We’ll start work once the storm dies down,’ he replied angrily.

‘But we’ve never seen anything like this before.’

‘I’m not responsible for winds,’ he said.

They began to imagine a number of possibilities. Copious tears flowed. One man was eager to share in the unknown, and started telling the people with him about a dream he had had the day before, as the storm grew more and more violent. Another man who had reached the limits of despair shouted that we should forget about dreams. Reality had now surpassed any dream.

The storm raged until sunset; some people said, until nightfall. It went away just as it had arrived – no guesswork, no conjectures. Good God! The world resorted to heavy silence, as though that same silence were an expression of regret. Now there arose the din of survival as lights started to shine from windows and corners. The entire quarter heaved one huge, long sigh, one in which every single soul participated.

‘What’s lost is lost,’ said Sheikh Bahiyya with a sob. ‘It can be replaced.’

The Head of the Quarter grew angry.

‘That’s enough doom and gloom!’ he yelled. ‘Everyone has had enough.’

But the voices that reacted were tinged with despair. Destruction, looting, robbery, money gone, reputations lost.

The Head of the Quarter became more and more worried as he listened to these comments. Some of them confirmed that robbers had indeed crawled out of ditches, holes and utterly unexpected places. There were so many and they were so concentrated that they blocked out the sun. They had taken full advantage of the storm blowing; indeed some people claimed that they were the ones who had stirred it up and called it down from its usual place in the skies.

All this caused a ruckus and great sorrow. The feeling of desperation no longer discriminated between Sheikh Bahiya and the Head of the Quarter.

A small group of people, whose clothes were still white, gathered by the door of the old fort. They were exchanging whispers, shaking hands in the dark, waiting resolutely and impatiently for dawn.

THE END OF BOSS SAQR

That night, reality hit like a dream. Boss Saqr, aged seventy, with his bride Halima, aged twenty, arrived at the second floor of his house to usher in the first of his honeymoon nights. On the floor below, his first wife, the mother of his children, was sitting with her son, Ragab. They were silent and morose, sharing thoughts. The mother felt crushed by mountains of anxiety, while Ragab’s face was flushed with anger.

‘Unbelievable!’ he said, staring at the ceiling.

‘These days,’ his aged mother replied, ‘everything’s unbelievable.’

‘It’s likely to collapse very soon.’

‘I pray to God that he’s still got a bit of sense.’

‘What’s scary is that all his money is in the safe in his bedroom.’

‘He’ll never forget that he’s responsible for five girls and a boy.’

‘I’m really sorry,’ Ragab shouted angrily, ‘that I never learned anything, or went to work.’

‘You’re his only son,’ she replied. ‘He didn’t want to overburden you.’

‘If he were really concerned about me,’ he said, ‘he would not be committing my fate to the mercy of a rapacious girl.’

‘Don’t get angry. We’ll only lose.’

‘We must do something.’

‘Think carefully. There has to be some kind of hope.’

The young man thought for a while.

‘The solution is for him to give me, my sisters and you our legal due.’

‘That

’s a reasonable request, but it will make him angry.’

‘If we get scared, we’ll lose out.’

‘We have to act sensibly, otherwise it’ll be two defeats, not one.’

All their lives, father and son had enjoyed everything that was fine and wonderful. Until this young girl had come along, his father had loved him more than anything else in the whole world. With that intense love, he had spoiled him, corrupted him, left him to face the world with no knowledge and no job. The safe had served as his security, until this girl had it clutched to her bosom. From now on, there was no hope.

Ragab found a potential outlet with the Head of the Quarter. He respected him as an old friend of his father’s, so he went to see him and shared his worries.

‘Forgive me for asking you,’ he told the Head of the Quarter, ‘but it’s better that you talk to him.’

‘Out of respect for neighbourliness and affection,’ he replied, ‘I’ll do my very best. May God grant me success!’

After Friday prayers, the Head of the Quarter took the Boss aside and offered him advice about what would be just and correct. The Boss was furious.

‘Do they want to inherit from me before I’m dead?’ he shouted. ‘This is the Devil’s handiwork!’

Ragab expected his father to summon and upbraid him. But instead, he ignored his son and cut him off. This affected him deeply; he was haunted by fears, awake and asleep. He made up his mind to defend himself, his mother and his sisters. He was pondering what he needed to do, but events anticipated him. Boss Saqr returned home from an anniversary party to find the house and the safe empty. Such was his fury that people soon heard the news: it became clear that the girl had run off with her cousin. Friends and neighbours in the quarter spread out to search for them, but Boss Saqr collapsed between life and death and took the wretched crew back to his room.

‘He’s going to abandon us to ruin,’ Ragab whispered in his mother’s ear.

‘We need to take care of him now,’ she replied sadly, ‘and let God’s will be done!’

The Boss now remained in a state of semi-consciousness, no longer regretting anything. In a moment of wakefulness he recognised his wife and children. His wife had the impression that he wanted to say something and put her ear close to his mouth.

‘Over the bath,’ he whispered.

The Boss died, but it was several days before calm returned to his house. All that time the family kept wondering what the dead man had meant by referring to the loft over the bath.

Ragab decided he needed to investigate his father’s statement. He climbed the wooden ladder into the loft, holding a gas lamp. He was greeted by spiders’ webs, but the mice scuttled off. His eager eyes spotted a chest resting in timeless tranquillity.

When opened, it revealed a pile of golden guineas.

LIFE IS A GAME

I was visiting Ali Zaidan to congratulate him on his latest promotion in the company.

‘I’ve repented,’ he said. ‘May God forgive what’s happened in the past.’

‘I’ve heard you say that many times before,’ I replied dubiously.

‘But this time,’ he told me confidently, ‘it comes with a solid determination.’

‘Did one of the players fold, I wonder, or have some of your companions been conspiring against you?’

‘What’s so powerful this time is that the feeling’s taken control of me for no specific reason. I’m motivated to transform my rotten life and welcome a new one.’

When he awoke from his feverish vertigo, he discovered that he was almost in his fifties and a stranger in our world, with no money saved to depend on, but instead a career that reeked of ill repute. He started to keep me company and initiate conversation, so as to discover the world anew and involve himself in people’s business and concerns.

‘The most precious thing I lost at the gambling table,’ he once told me, when he was at his most anxious, ‘was my life, not the money.’

‘Life begins at sixty,’ I told him, by way of consolation.

‘I want to get married,’ he told me, in all seriousness.

‘There’s a suitable bride for every age,’ I said.

‘I’ve spoken to my sister, Afkar, because she was always the first one to urge me to get married. But I want to get married in the genuine sense.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I’m not looking for left-overs from a parfumier! What I’d like is a young virgin bride, reasonably good-looking and with some education.’

‘These days marriage is expensive,’ I told him frankly.

‘Things can be arranged,’ he replied, his voice scornful, ‘through an advanced contract backed by my salary, which is not at all bad.’

‘That’s fine then. Isn’t there a woman in your life?’

‘I’ve never had any time for love,’ he replied with a laugh tainted by bitterness.

A joint effort now began involving Afkar Hanem and me. We would begin the conversation by talking about his position and salary; that certainly aroused the listener’s appetite for more. But when his career was mentioned, eyebrows went up, accompanied by a scowl. No sooner was the name Ali Zaidan uttered than the cry ‘You mean, that gambler?’ assaulted our ears. In fact, I came to realise that some people, although willing to overlook theft and bribery, were appalled by gambling and gamblers.

This news had to be shared with my friend. He was both sad and sorry and I had the impression that he was ageing twice as fast as before.

‘I’m not going to leave this world,’ he challenged me, ‘unless I’m a husband and father.’

‘We needn’t despair,’ I replied amiably.

‘Now I have something to depend on. I’ve been to visit Sheikh Labib, and he’s read the unseen for me.’

I could not help laughing.

‘I didn’t realise you were someone who believed in such men,’ I said.

‘Despair can lead to worse than that,’ he replied with a sigh.

Sheikh Labib was telling the truth. Sitt Dalal, of evil reputation, renowned in our quarter, had heard about my friend’s problem. She had a twenty-yearold daughter, a model of both beauty and liberation, who was arousing the quarter’s anger. Sitt Dalal now decided to add this discarded entity to her own family. She tossed Suad, the beautiful young girl, into the old man’s path, unperturbed by the whispers, leers, and winks. The old man, who was angry and desperate, fell into the golden trap. He paid no attention to his family’s protests and lost all his friends, instead becoming one of the quarter’s most intriguing stories.

‘I’m not going to let anyone ruin my happiness,’ he told me with a meaningless laugh, ‘now that this sudden opportunity has arisen.’ Seizing my hands, he added, ‘I’m grateful to you for sticking by me and giving me your friendship. I hope that you too are convinced: whenever you accept a glass, you drink it to the dregs.’

The years went by, and Ali Zaidan had a son and two daughters. When he retired, his children managed to distract him from his worsening poverty. With her beauty his wife distracted him from everything else. His house became proverbial. Whenever things were tough, he would say ‘I’m still losing at the gambling table’.

LATE NIGHT SECRET

He returned to the quarter a little before dawn. The quarter seemed sound asleep, eyelids firmly shut. At that hour, his tottering shadow was all that was visible in the night’s darkness. He progressed cautiously until he entered a field which gave off a magical scent. Where could this fragrant perfume be coming from? It was his senses that were roused to respond:

‘The trail of a woman passing, the trace left by a female as she crossed from one side to the other. Why am I immersed in darkness at this time of night? On my own, guided only by my throbbing heart and an unknown destiny.’

His heart was filled with an aroma so sensually thrilling it overwhelmed him. For a while, his feet remained rooted to the ground, but then he began to walk slowly to and fro in the quarter as though he were a night watchman.

Had he arrived a few minutes earlier, he might well have seen a rare sight in the final hours of the night. It might well have been something quite normal, far removed from his lively imagination.

Even so, he was still inclined to follow the wild idea that would conjure an adventure from this atmosphere. He expected some secret to be exposed in this quarter, so shrouded in piety and the counsels of the righteous. Morning or evening, whenever a woman passed by, he would remember, sniff, and sigh. Then he would sniff again.

THE PRAYER OF SHEIKH QAF

Umaira al-Ayiq had been murdered.

Hifni al-Rayiq was accused of the crime.

Al-Zayni, Kibrita, and Fayiq all witnessed the crime and testified to it.

Hifni al-Rayiq confessed to the crime. People looked amazed as they compared the victim’s huge size with the tiny body of the killer.

‘He pounced on me,’ Hifni said, ‘but I got away. I threw a stone at him, and it killed him.’

Those who do not believe in fate were prepared to believe him. In spite of the victim’s status, people regarded the incident as closed. All that remained was to await the verdict.

But the quarter has its own hidden tongue, although no one knows to whom it belongs. It can whisper misgivings and reveal secrets. Such rumours persisted until they filled the entire atmosphere like a powerful smell. One such rumour, terse and obscure, stated that Al-Rayiq did not murder Al-Ayiq; Al-Zaini, Kibrita, and Fayiq were all false witnesses. Not only that, but Al-Rayiq was falsely testifying against himself, as sometimes happens in our quarter’s folklore.

‘Have you heard what’s being said about the Al-Ayiq murder?’ the mosque Imam asked the Head of the Quarter.

‘There’s no end to our quarter’s folktales,’ the Head of the Quarter replied with a frown.

The Head of the Quarter slunk over to Sheikh Qaf’s house, cradle of blessings and readings of the unseen.

‘There’s not a single man or woman in our quarter,’ he said, approaching the Sheikh, ‘who hasn’t come to this room for a private consultation. You know a lot of things that we don’t.’

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

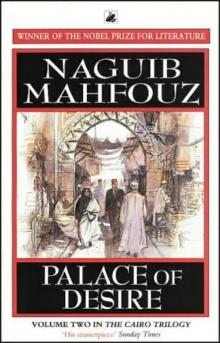

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma