- Home

- Naguib Mahfouz

Morning and Evening Talk Page 9

Morning and Evening Talk Read online

Page 9

Surur was dazzled by his wife’s beauty, calm nature, and gentle disposition. With her he found love and gratification and, over the course of a prosperous marriage, she gave birth to Labib, Gamila, Bahiga, Zayna, Amir, and Hazim. Surur’s government job, excellent wife, and beautiful children paved the way for equanimity. However, he always dwelled on what he lacked so was often corrupted by fantasies, and envy united his heart and tongue. He and Zaynab were united by something that she hid with her calm nature and gentle disposition and he revealed with his careless mannishness. He knew—it was impossible not to—what his grandfather Ata al-Murakibi had been and how he had become who he was, how destiny had smiled on him, just as he knew where his uncle Dawud’s “Pasha” title came from. He objected to his grandfather’s wealth and his mother’s poverty, accusing him of depravity and cruelty, and he burned with jealousy of his beloved brother, Amr, because everyone showered affection and gifts on him while he, Surur, was ignored as though he were not Amr’s brother, forgetting that it was his own vicious tongue that deterred people. His aggravation was compounded when Amr passed over his two daughters and married his two sons into the families of Dawud and al-Murakibi. Yet any resentment between the two brothers and their two families remained beneath the surface and love always conquered, even if deep down conflicting frustrations often surged. Even Radia and Zaynab’s differences were concealed by ongoing peace and good relations. Surur wept passionately the day Amr died, and Zaynab passed away beneath an awning of Radia’s recitation and tears.

In the same way that Surur was less pious than his brother, so he was less patriotic. However, the 1919 Revolution lodged in his insubordinate heart a warmth that would remain with him to his dying breath. He persistently boasted about his part in the civil servants’ strike, as though he had been the only person to strike, and memories of the demonstrations lived on in his imagination as one of the delights he most savored from his life. The violent wave clamoring with anthems of glory swept with it father and son and burst into the hearts of the women behind the mashrabiya. He thus found in the Murakibi and Dawud families’ renunciation of its hallowed leaders a target upon which he could unreservedly unleash his tongue. “We have an uncle who worships nothing in the world but his self-interest,” he would say to his brother. Or, “The great house of Dawud has joined Adli under the illusion that they are really part of the aristocracy!”

In middle age another revolution exploded in Surur, which entailed a revolt against his wife’s love. His eyes and impulses burst out in pursuit of adolescent fantasies and a rift developed between him and the meek, loving, sorrowful Zaynab.

“What will we do if one of our neighbors complains about you to her husband?” she would reprimand him in a whisper.

“There is nothing to complain about,” he would retort.

When she complained to Amr, Surur poured anger on her and threatened he could marry again whenever he liked, though a second marriage was really an impossible dream. In fact he only betrayed his wife twice—once in a brothel, and then in a short fling that lasted no more than a week. He increasingly resented his poverty and his boorish grandfather even more. He tirelessly bought lottery tickets, but gained nothing from it other than the silent reproach glimmering in the eyes of his eldest son, Labib, and daughters, especially after Zaynab’s health deteriorated. When Amr died, loneliness and depression descended on him, and when the war, the darkness, and the air raids came, he declared life a raw deal. His only consolation was his son Labib‘s success, but his constant boasting about it made him a heavier weight on the family’s hearts. In later life, he stopped going to see the Murakibi and Dawud families but would often visit Amr’s sons and daughters, just as he would his sister’s house, and joined in their joys and sorrows. They had been fond of him since they were young, and became even more so when their own father died. One autumn evening in his final year of government service, as he sat behind the mashrabiya gazing out at the dark cowering above the houses and minarets, expecting the usual air raid siren to come at any minute, he had a heart attack. His life was over in less than a minute.

Salim Hussein Qabil

The last child of Samira Amr and Hussein Qabil, he was born and grew up on Ibn Khaldun Street. His father died when he was only a year old so he was brought up in a disciplined climate, nothing like the comfortable lifestyle his family had enjoyed when he was just a glimmer on the horizon. He was good looking like his mother and tall like his father, and had a large head and intellect like his brother Hakim. His obstinacy and stubbornness, as well as his talent in school, came to light in childhood. His sister Hanuma watched over him closely with her piety and strict morality, and for a long time he believed he was learning the truth about the Unknown from the lips of his grandmother Radia. He loved football and was good at it, enjoyed mixing with girls in al-Zahir Baybars Garden, and hated the English. Dreams of reform and the perfect city toyed constantly with his imagination. He did not incline to any one party, deterred by his brother Hakim, who rejected everything outright. He once heard Hakim say, “We need something new,” and replied automatically, “Like Caliph Omar ibn al-Khattab.”

His own temperament and Hanuma’s influence prompted him to turn to the religious books in his brother’s library. His dream of the perfect city vanquished football and girls. He was in secondary school for the July Revolution and welcomed it eagerly, like deliverance from annihilation. The role his brother Hakim played in it strengthened his commitment and, for the first time, it seemed to him the perfect city was being built, brick by brick. He thought that by joining the Muslim Brotherhood he could immerse himself further in the revolution, but when the revolution and the Brothers came into conflict his heart remained with the latter. Disagreement emerged between him and his brother. “Be careful,” Hakim said.

“Caution can’t save us from fate,” Salim replied.

He entered law school and his political—or rather religious—activities increased. But none of his family imagined he would be among the accused in the great case against the Muslim Brothers. Hakim was dismayed. “It’s out of our hands!” he said to his anxious mother. Salim was sentenced to ten years in jail. Samira reeled at the force of the blow; Hakim’s shining star could not console her for his brother’s incarceration. She secretly despised the revolution, and Radia invoked evil on it and its men.

Salim was released from prison a year before June 5, completed the remainder of his studies, earned a degree, and started work in the office of an important Muslim Brotherhood attorney. He saw the great defeat as divine punishment for an infidel government. He did not sever links with his accomplices but conducted his business with extreme secrecy and caution. He found relief in writing and devoted years of his life to it. His labors bore fruit in his book, The Golden Age of Islam, which he followed with a work on the steadfast and pious. At the same time, he achieved considerable success as a lawyer and, with the sales of his two books, his finances improved, especially after Saudi Arabia purchased a large number of them. When the revolution’s leader died, he recovered a certain repose. Samira said to him, “It’s time you thought of marrying.” He responded eagerly, so she said, “You must see Hadiya, your aunt Matariya’s granddaughter through Amana.”

Hadiya was the youngest of Amana’s children. She had recently returned from the Gulf after teaching there for two years and had purchased an apartment in Manshiyat al-Bakri. He went with Samira to Abd al-Rahman Amin and Amana’s house on Azhar Street and saw Hadiya, a fine looking teacher in the prime of youth, whose beauty was very much like her grandmother Matariya’s, the most beautiful woman in the family. Samira proposed to her on his behalf, she was wedded to him, and he moved to her apartment in Manshiyat al-Bakri. He had a lovely wife and flourishing career. He knew love and compassion under Sadat and had no cause for worry other than the new religious currents that had emerged within the Brothers, cleaving new paths surrounded by radicalism and abstruseness. “There is a general Islamic awakening, no doubt ab

out it. But it is also resurrecting old differences which are consuming its strengths to no avail,” he said to his brother Hakim. However, Hakim had other priorities and, despite his personal feelings, saw what befell the regime on June 5 as an absolute catastrophe; the nation was moving into uncharted territory. As the days went by, God granted Salim fatherhood, material abundance, and satisfaction on the day of victory. Yet none of this jostled from his heart his deeply rooted belief in, and eternal dream of, the divine perfect city. He swept Hadiya along in his forceful current until she said, “I was lost and you showed me the right way. Praise be to God.”

Salim became a propagandist writer for the Muslim Brotherhood’s magazine and, like the rest of the group, was filled with rage at Sadat’s reckless venture to make peace with Israel. He reverted once more to vehement anger and rebellion, and when the September 1981 rulings were issued he was thrown back in jail. When Sadat was assassinated he said, “It’s a divine punishment for an infidel government.”

He could breathe freely in the new climate but had lost confidence in everything except his dream. It was for this that he worked and lived.

Samira Amr Aziz

She was Amr’s fourth child and second only to Matariya in beauty. As she played on the roof and beneath the walnut trees in the square and studied at Qur’an school, her serious personality, calm nature, and brilliant mind crystallized. She seldom got involved in quarrels with her siblings and when violence flared up would withdraw into a corner, content to watch what she would later be summoned to bear witness to. Though more beautiful, she resembled her mother in general appearance—except for her height, at which Radia greatly marveled. In contrast to her sisters, she retained the principles of reading and writing that she learned at Qur’an school and nurtured them diligently, so she was the only one to regularly read newspapers and magazines as an adult. On visits to the Murakibi family at the mansion on Khayrat Square and the Dawud family in East Abbasiya, she made a mental note of the elegant setup, table manners, rhythm of conversation, and beautiful style and tried to adopt and emulate them as far as means and circumstances allowed. Mahmud Bey would joke in his crude manner, “You’re a peasant family, but there is a European girl in your midst!”

She entered adolescence but did not have to dream secretly of romance for long, for a friend of her brother Amer called Hussein Qabil, who owned an antique shop in Khan al-Khalili, came and asked for her hand. He had kept her brother company up to the baccalaureate then taken over from his father when he died. Despite his youth, his manly features catapulted him into manhood early. He had a huge body, a large head, and sharp eyes, and was generous and very well-off. Unlike Sadriya and Matariya, Samira was wedded to her husband in an outer suburb, in one of the apartments of a new building on Ibn Khaldun Street. This suited her very well for she met many Jewish families, learned how to play the piano, and raised a puppy called Lolli that she would take with her on walks around al-Zahir Baybars Garden. When Amr heard about this he said, both protesting and accepting the situation, “It’s God’s will. There is no power or strength but in God.”

Hussein Qabil was wealthy and generous, so fountains of luxury burst forth in his house and Samira could gratify her hidden longing for style and elegant living. Her happiness was compounded by her husband’s good company and manners, and the fact that he addressed her as “Samira Hanem” in front of others while she called him “Hussein Bey.” Sincere patriotism and deep piety filled the man’s heart and he spread them to everyone around him, and so the 1919 Revolution penetrated Samira’s heart in a way it did not the hearts of her sisters. Similarly, her piety was the most sound of the young women because she was the least influenced by Radia’s mysteries. She gave birth to Badriya, Safa, Hakim, Faruq, Hanuma, and Salim, all of whom enjoyed a generous share of beauty and intelligence. The parents worked together to bring them up well in an atmosphere of religion and principle. From the first day she said to Hussein Qabil, “We will educate the girls along with the boys.” He agreed enthusiastically.

Samira’s glow was enough to stir jealousy among the Murakibi and Dawud families. Yet her life was not devoid of great sorrow, for she lost Badriya and Hakim and his family, and anxiety about Salim broke her heart at various points in her life. Astonishingly, she met these calamities with a strong, patient, and faithful will and was able to confront and endure them. But the forbearance with which she endured her sorrow also made her vulnerable to accusations of coldness.

“You should believe in amulets, spells, incense, and tombs. There is no knowledge but that of the forefathers,” Radia said to her. Samira secretly asked herself whether it was these that had protected Sadriya and Matariya from calamities.

Death came and Hussein Qabil died a year after Salim was born, four years after her own father’s death. He left her nothing except a depository of antiques. She sold them as the need arose and lived on the proceeds. He died just as his children were moving from secondary school to university.

“What’s left for you now, Samira?” Radia asked.

“A depository of antiques,” she replied.

“No, you still have the Creator of heaven and earth,” said her mother.

Shazli Muhammad Ibrahim

THE SECOND SON OF MATARIYA and Muhammad Ibrahim, he was born and grew up in his parents’ house in Watawit. He was good looking, but less so than his deceased brother, Ahmad. He took his brother’s place as his uncle Qasim’s playmate but did not achieve the same legendary status. From childhood, he frequented the house of his grandfather Amr and the families of Surur, al-Murakibi, and Dawud and continued to do so throughout his life, borrowing his love of people and socializing from his mother. From childhood too, attributes that would accompany him through life manifested: amiability, a penchant for fun, hunger for knowledge, love of girls, and all-round success in all of these, though his academic achievements were only average. His love of knowledge probably came from his father and it prospered with the books and magazines he procured for himself. Besides his relatives, he made friends with the leading thinkers of the day, who woke him from slumber and inflamed him with questions that would dog him all his life. Despite his burgeoning humanism, he inclined to mathematics so entered the faculty of science, then became a teacher like his father, remaining in Cairo thanks to the intercession of the Murakibi and Dawud families. He proceeded through life concerned with his culture and oblivious to the future until his father said to him, “You’re a teacher. The teaching profession is traditional. You should start thinking about marriage.”

“There are lots of girls in the family—your aunts’ daughters and our uncle’s daughter, Zayna,” said Matariya.

He had casually courted a number of girls but did not have genuine feelings for any of them.

“I’ll marry as it suits me,” he said.

“A teacher must maintain a good reputation,” his father cautioned.

“A ‘good reputation’?” He was going through a period when he questioned the meaning of everything, even a “good reputation.” Whenever he was alone he would ask himself the question: Who am I? His thirst to define his relationship to existence was obsessive and consuming. He never stopped debating with people, especially those in whom he recognized a taste for it, like his cousin Hakim and other young men in the families of al-Murakibi, Dawud, and Surur. Later he ventured to have audiences with Taha Hussein, al-Aqqad, al-Mazini, Haykal, Salama Musa, and Shaykh Mustafa Abd al-Raziq. He did not reject religion but sought to base himself in reason as far as possible. Every day he had a new concern. He would even hold discussions and confide in his uncle Qasim and interrogate relatives in their graves on cemetery festivals.

When his grandfather Amr was carried to bed breathing his last, a nurse called Suhayr was brought to administer an injection. Shazli fell in love with her despite the grief that reigned. He helped her heat some water while his uncle Amer’s wife, Iffat, quietly observed them with a sly, wicked look in her eyes. As the 1940s approached, their lo

ve cemented. He realized he was more serious than he had imagined this time and announced his wish to marry. Matariya said frankly, “Your face is handsome but your taste is appalling!”

He responded to the rebuke with a laugh.

“Her roots are lowly and her appearance is commonplace,” Matariya went on.

“Prepare for the wedding,” he said to her.

Muhammad Ibrahim accepted the situation unperturbed and Matariya did not dare to anger her son beyond what she had said already. Shazli selected an apartment in a new building on Abu Khuda Street and embarked on a life of love and matrimony. Suhayr gave up her job and devoted herself to married life. She proved elegant and agreeable and soon won her mother-in-law’s acceptance. Shazli was unlucky with his children; five died in infancy and the only one to live, Muhammad, became an army officer and was martyred in the Tripartite Aggression. Shazli spent his life searching for himself. He would read, debate, and question, only to hit a wall of skepticism and begin the game again. He was not interested in politics, except insofar as events that invited reflection and understanding, and so did not fall under the magic of the Wafd but followed the ups and downs of the July Revolution as one might an emotive film in the cinema. Yet he was disconsolate to lose Muhammad and never recovered from his grief. “Neither of us was created for pure happiness,” he once said to his sister, Amana. He found some solace in loving her children. He was fearful of the severity and vehemence of his cousin Salim, his niece Hadiya’s husband, and found neither enjoyment nor pleasure in his conversation. Salim said to him, “Your confusion is a foreign import. It shouldn’t trouble a Muslim.”

Miramar

Miramar The Mummy Awakens

The Mummy Awakens The Beginning and the End

The Beginning and the End Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search

Respected Sir, Wedding Song, the Search The Mirage

The Mirage Novels by Naguib Mahfouz

Novels by Naguib Mahfouz Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile Karnak Café

Karnak Café Heart of the Night

Heart of the Night Before the Throne

Before the Throne The Time and the Place: And Other Stories

The Time and the Place: And Other Stories Cairo Modern

Cairo Modern Arabian Nights and Days

Arabian Nights and Days The Day the Leader Was Killed

The Day the Leader Was Killed Morning and Evening Talk

Morning and Evening Talk Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth Children of the Alley

Children of the Alley Voices From the Other World

Voices From the Other World The Harafish

The Harafish The Quarter

The Quarter The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales

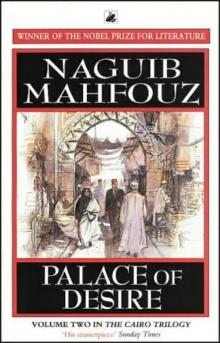

The Seventh Heaven: Supernatural Tales The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street

The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street Khan Al-Khalili

Khan Al-Khalili Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War Three Novels of Ancient Egypt

Three Novels of Ancient Egypt The Time and the Place

The Time and the Place Palace Walk tct-1

Palace Walk tct-1 Akhenaten

Akhenaten The Seventh Heaven

The Seventh Heaven The Thief and the Dogs

The Thief and the Dogs The Cairo Trilogy

The Cairo Trilogy Sugar Street tct-3

Sugar Street tct-3 Palace of Desire tct-2

Palace of Desire tct-2 The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma